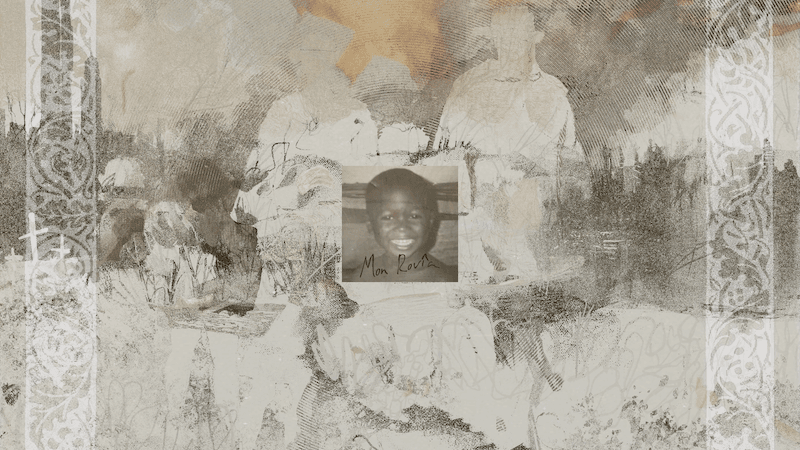

On Bloodline, singer-songwriter Mon Rovîa approaches his complex upbringing with an impressive clarity of vision. Born in Liberia during the West African nation’s civil war, Janjay Lowe was adopted by a white American family that moved around the U.S.; eventually, Lowe would come to call Tennessee home. As a teen, he picked up his brothers’ taste for Fleet Foxes and Bon Iver, but seeing few Black artists working in that genre, Lowe started making R&B. As he found a TikTok following, he gradually re-introduced those indie-folk influences, embracing the ukulele he’d played as a kid and coming to recognize his place in a long lineage of Afro-Appalachian music. Bloodline, his full-length debut, follows a series of EPs and represents his most direct reckoning with his backstory in song.

A recent NPR story about modern protest singers who got their start on TikTok included Mon Rovîa alongside Jesse Welles and Jensen McRae. Mon Rovîa’s music falls somewhere between the former’s state-of-the-world polemics and the latter’s more introspective style; in particular, Lowe shares McRae’s proclivity for mellow 2000s adult-alternative songwriting. But in these songs, that familiar palette of soothing guitar and fiddle clashes with graphic lyrics. Take “Day at the Soccer Fields,” where Lowe sings about traumatic childhood memories over a sliding string bed: “I remember it/Like it was yesterday/AK‑40 pointed at my face.” The dissonance gets outright uncomfortable on “Running Boy,” where a dangerous police encounter intrudes on a singalong chorus as Lowe describes feelings of survivor’s guilt. The approach functions like a Trojan horse (how else would you sneak an anti-genocide song onto CBS under right-wing siege?), but in context, it also feels like a method of self-soothing.

The album’s most fascinating moments come when Lowe examines his double consciousness, as he reconciles his early Liberian childhood with his American adolescence. (The challenge is aptly represented in his choice of stage name: Liberia’s capital city, Monrovia, is named for American President James Monroe, a prominent supporter of the 1800s colonization movement that sent free Black people from America to Liberia.) Lowe tackles this question most poignantly on “Whose Face Am I,” where he wrestles with not knowing his birth parents before adoption: “Trying to give meaning to phantom feelings/Yearning in my soul, for a name I’ll never know.” On “Somewhere Down in Georgia,” he places his experience of life in the American South in the wider context of Black trauma in the region: “Cotton fields turned parking lots/Steel and stone can’t hide these stains/History grows in the cracks when it rains.” Even when the song shifts tempos and sounds more hopeful, Lowe offers no easy answers.

Still, it’s strange to hear this complexity turned into catchy choruses, which illustrates the album’s central tension: the attempt to find peace in a fractured identity. At 16 tracks, Bloodline occasionally lapses into more generic imagery about overcoming fear—such as on “Oh Wide World”—and messages that are heartfelt but less pointed. “Heavy Foot” admirably looks outward, but engaging with complex global issues like the prison industrial complex and the Gaza genocide in back-to-back verses calls for more substantial scaffolding than a simple “they’re never gonna keep us down” stomp-clap chorus can provide. The album’s most purely beautiful, hopeful track successfully turns its gaze toward larger struggles: “Pray the Devil Back to Hell,” which shares its title with a documentary about an interfaith group of Liberian women who pressured the country’s then-president into a 2003 peace agreement, ending the civil war. It’s a captivating story, told simply and literally in Lowe’s song, with a counterpoint and percussion to give the story scale. It’s easy enough to see the parallels to Mon Rovîa’s mission: staring down the worst of humanity’s violence and meeting it with peace.