A few months and ago, a war broke out. Yes, we are already fed up with those, but this time it was not a war in the literal sense. It was a bidding war. That is the accepted Hollywood term for a struggle between studios and producers over intellectual property that is up for sale. This time, however, the violent metaphor feels disturbingly appropriate, since the property in question is the rights to one of the most terrifying, talked-about and influential horror films of all time: “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre,” Tobe Hooper’s boundary-shattering independent film from 1974.

At the last Jerusalem Film Festival, currently underway, a tribute to the iconic film is being held, with a screening scheduled for Tuesday night alongside the documentary “Chain Reactions,” which brings together prominent filmmakers and artists, including Stephen King, Japanese provocateur Takashi Miike and comedian Patton Oswalt, to discuss the film’s lasting impact on their work.

e Texas Chain Saw Massacre’: trailer

(youtub)

But back to the rights. Take a look at some of the names battling for them: modern horror maestro Jordan Peele (“Get Out”), “Yellowstone” empire chief Taylor Sheridan, a proud Texan, rising horror director Oz Perkins (“Longlegs,” “The Monkey”), “Minecraft: The Movie” producer Roy Lee, and actor Glen Powell, one of Hollywood’s most sought-after stars of the past few years and another proud Texan.

There are more heavyweight contenders involved, and the high-profile nature of the race underscores the commercial appeal of “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre” brand more than half a century after the original film’s release. To date, eight films have been released under the franchise, not including the original. The most recent entry, unimaginatively titled “Texas Chainsaw Massacre,” debuted on Netflix in 2022.

Together with the 1974 original, the series has grossed more than $250 million worldwide on a combined budget of just over $50 million. Add to that books, comic books, video games, toys and even a themed attraction at Universal’s new horror park in Las Vegas, scheduled to open in late August, and the sums grow even larger. The bottom line is clear. This is a highly profitable franchise, and in the right hands it can remain so. Fingers crossed for you, Jordan Peele.

10 View gallery

Still making money. And lots of it. From ‘The Texas Chain Saw Massacre’

(Photo: Courtesy of the Jerusalem Film Festival))

But the financial potential of “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre” is not the whole story. Its elevated status is not rooted primarily in money. The true heart of the matter is its cultural legacy. Its bleeding heart, to be precise.

By the time “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre” arrived in 1974, Hollywood had already undergone a major shift in how violence and sex were portrayed on screen. Arthur Penn’s “Bonnie and Clyde” in 1967 was a watershed moment, bringing graphic violence into the mainstream and earning two Academy Awards. Sam Peckinpah’s “The Wild Bunch” pushed things even further, followed by “A Clockwork Orange” in 1971, “The Godfather” in 1972 and “The Exorcist” in 1973.

10 View gallery

This is where everything began to change. From ‘Bonnie and Clyde’

At the same time, exploitation films such as Wes Craven’s “The Last House on the Left” were breaking into broader circulation. Encouraged by the success of these films and by the rise of the so-called New Hollywood generation, studios abandoned the outdated Hays Code, which had served as Hollywood’s system of self-censorship since the 1920s. Suddenly, it seemed there were no rules left.

Hooper, who died in 2017, conceived the film in the early 1970s while working as a teaching assistant in the University of Texas film department. Inspired by the crimes of serial killer Ed Gein, who was convicted of two murders and suspected of several more, and by a shared sense of disillusionment with America, Hooper teamed up with fellow University of Texas alumnus Kim Henkel. The two wrote the screenplay and cast friends and acquaintances from Austin. A piece of trivia that is charming but entirely unnecessary: actor John Larroquette, who did not appear on screen but narrated the film and later became famous for the sitcom “Night Court,” was paid in marijuana. Not a bad deal.

10 View gallery

From ‘The Texas Chain Saw Massacre’

(Photo: The Jerusalem Film Festival))

The shoot itself was grueling, filmed in Texas heat approaching 104 degrees Fahrenheit, with 16-hour days. The original budget of $60,000 quickly proved unrealistic. By the time editing was complete, the final cost ranged somewhere between $93,000 and $300,000. Still a pittance. Finding a distributor proved difficult. Eventually, the rights were acquired by Bryanston, a company known for low-budget science fiction and horror, but best known for distributing the pornographic phenomenon “Deep Throat” in 1972. Despite the massive revenues from both films, Bryanston collapsed in 1976 amid lawsuits and alleged ties to organized crime.

The film premiered on October 1, 1974, in Austin, marketed as being based on a true story, a claim that fueled its notoriety. It went on to gross more than $30 million, an enormous sum for a horror film at the time. Hooper was shocked when the MPAA initially gave the film an X rating, later reduced to R after several cuts.

10 View gallery

The British were not fans. From ‘The Texas Chain Saw Massacre’

(Photo: The Jerusalem Film Festival))

Even so, the film was banned in numerous countries, including Britain, where the ban lasted until 1998. Other countries included Brazil, France, Norway, Sweden and West Germany. Australia finally released the film in 2021, Russia followed in 2024, and Poland screened it theatrically for the first time only in 2025.

So what was all the fuss about?

The plot is brutally simple. Five young people travel through rural Texas. They pick up a hitchhiker who turns violent. They discover a house in the middle of nowhere. One by one, they are killed by a large man wearing a mask made of human skin: Leatherface.

There is no backstory, no explanation, no psychological framework. The film offers no comfort, no meaning and no redemption. Its power lies in how violently it violates the unspoken contract between storyteller and audience.

10 View gallery

Ma’am, they only invited you to dinner. Why make a scene? From ‘The Texas Chain Saw Massacre’

(Photo: The Jerusalem Film Festival))

Over the years, critics and scholars have proposed countless interpretations, from vegetarian allegory to post-Vietnam despair to a critique of capitalism. Ultimately, the film’s enduring force comes from its moral ambiguity and relentless nihilism. The horror simply exists. Deal with it.

So yes, the dark magic of “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre” is clear. The film’s aggressive assault on its audience, the way it leaves viewers battered and bleeding without offering explanations, is unmistakable, at least for those willing to endure the experience. And it is safe to assume none of us need a psychological breakdown of the addictive pull of horror films or the catharsis they provide.

10 View gallery

We get it, dear cannibals. From ‘The Texas Chain Saw Massacre’

(Photo: The Jerusalem Film Festival))

But the more intriguing question remains unanswered. How did this film become a cultural phenomenon? What did it bring to the table that its predecessors either could not or did not dare to offer? After all, “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre” screened at the Cannes Film Festival in 1975, appears on virtually every list of the greatest horror films ever made, often at or near the top, and inspired countless genre entries that followed, from Ridley Scott’s “Alien,” whose director has acknowledged its influence, to Wes Craven’s “The Hills Have Eyes,” created by another devoted admirer.

How did something so repulsive and shocking lead figures such as Stephen King and Quentin Tarantino, who famously called it “one of the few perfect films ever made,” to openly profess their love for it and discuss it at length?

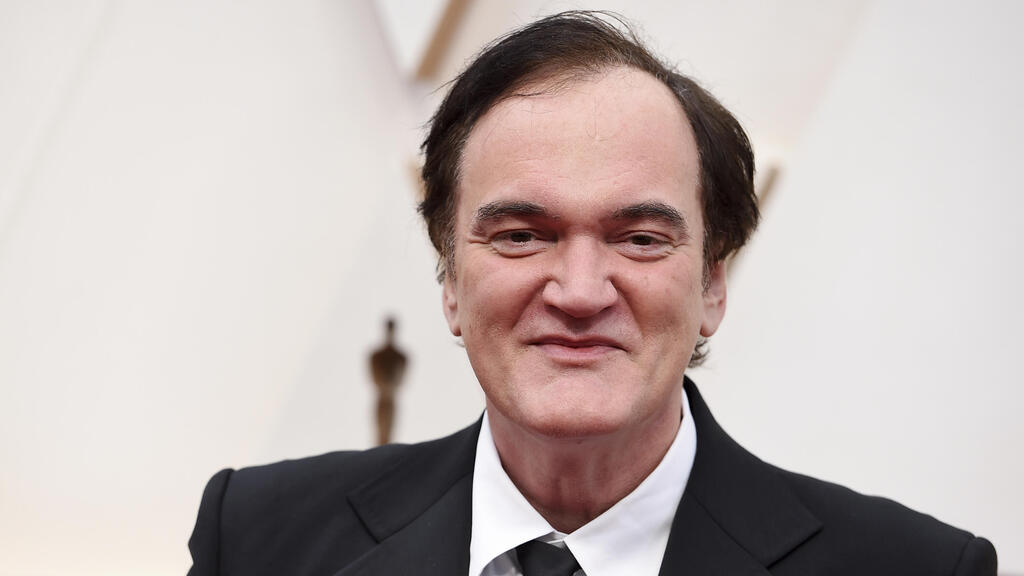

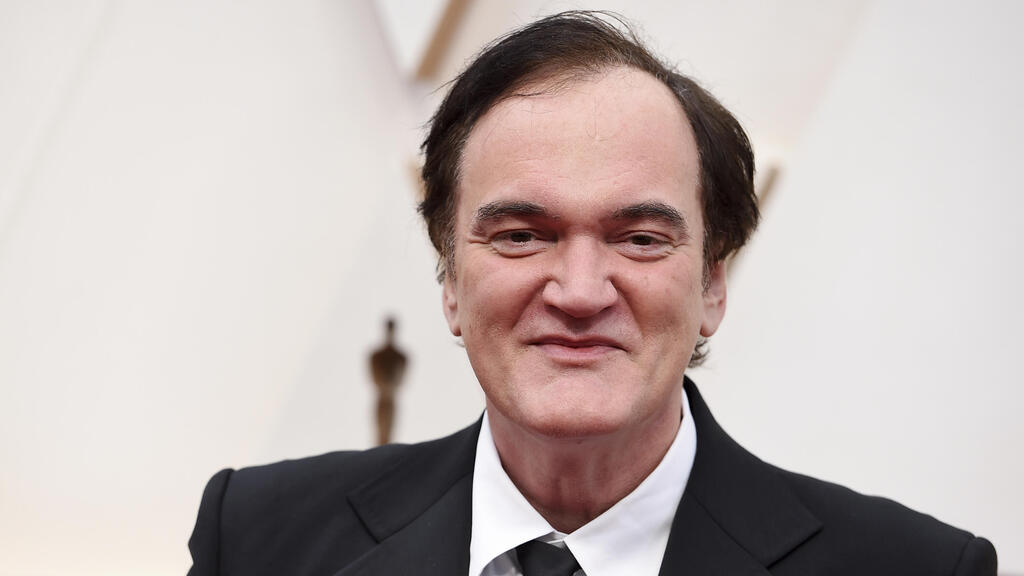

10 View gallery

Another admirer. Quentin Tarantino

(Photo: AP)

The most likely explanation lies in the film’s formalist approach. Hooper shot “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre” on 16mm rather than the wider, more conventionally cinematic 35mm format, and cinematographer Daniel Pearl gave the film a raw realism that was virtually unheard of in horror cinema at the time. For moviegoers in the 1970s, the horrors contained in “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre,” combined with Hooper and Pearl’s grainy, almost documentary-like aesthetic, hit like a hammer to the head.

10 View gallery

Hardcore horror seasoned with art-house sensibilities. From ‘The Texas Chain Saw Massacre’

(Photo: The Jerusalem Film Festival))

Within genre terms, it is easy to place “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre” in the tradition of blood-soaked grindhouse exploitation films, fast, cheap and designed for the smallest, dirtiest and sleaziest screens around. Yet in many respects, Hooper approached his carnage like an art-house filmmaker. He made deliberate use of the arid Texas landscape as a tool to heighten anxiety and dread, sharply contrasting it with the claustrophobic interior scenes inside Leatherface’s nightmarish home.

That dryness carries over into the sound design, which makes minimal use of music and instead gives center stage to the victims’ screams and the jarring sound of a chainsaw in action. There are also the long takes, which deny the viewer any relief from the horror, and Hooper’s remarkably astute choices regarding how violence is shown on screen.

As noted, for a horror film with such a notorious reputation, and compared with horror films in general, “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre” is surprisingly restrained when it comes to graphic violence. The violence that does appear is not stylized or choreographed, nor is it shot with visual flourish. The bloodshed is abrupt, crude and seemingly spontaneous, and precisely because of that, it is all the more convincing and terrifying.

Rivers of blood and severed limbs, so common in exploitation films of the era and those that followed? Not here, or rather, not at Tobe Hooper’s school. As truly skilled filmmakers understand, and as Steven Spielberg demonstrated in “Jaws,” released a year after “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre,” what you imagine is far more frightening than what you are shown.

10 View gallery

When sharp instincts meet a shoestring budget, Tobe Hooper, left, alongside director Takashi Miike

(Photo: Koichi Kamoshida/Getty Images)

Accordingly, Leatherface is often filmed from a distance as he carries out his butchery, or the violence unfolds with the victims’ backs turned to the camera. When Pam is impaled on the meat hook, we see her desperate reaction rather than a close-up of the act itself. As generations of traumatized viewers and outraged censors can attest, it is an extremely effective tactic, even if part of it can be attributed not only to Hooper’s sharp instincts, but also to the film’s limited budget, which made elaborate effects difficult to achieve.

The influence of “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre” on the genre it burst into, like a deranged cannibal, is difficult to quantify. It is commonly associated with the slasher subgenre, which four years later would be turned into a lasting cinematic phenomenon by John Carpenter’s “Halloween.”

Carpenter set his story in the American suburbs rather than the Texas wasteland, but he clearly borrowed several elements from Hooper, most notably the large, masked psychotic killer and the Final Girl trope, the lone female survivor who prevails through courage and resourcefulness. That template would be repeated in countless slasher films in the decades that followed.

Wes Craven, another admirer, created his own desert cannibal classic in 1977 with “The Hills Have Eyes,” later updated in a strong 2006 remake by French director Alexandre Aja. Musician and filmmaker Rob Zombie, himself a devoted fan, demonstrated his debt to Hooper’s horror classic in his Firefly trilogy: “House of 1000 Corpses” from 2003, “The Devil’s Rejects” from 2005 and the later, far less successful “3 From Hell” from 2019.

10 View gallery

Hey, Michael Myers, without Leatherface you would not exist. From ‘Halloween II’ (2009)

(Photo: yes)

And that is only the tip of the iceberg. The long-term influence of “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre,” particularly its naturalistic approach to horror, can also be seen in the wave of found-footage films that followed the massive success of “The Blair Witch Project” in 1999. Yet few of them, and indeed few horror films made either before or after “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre,” deliver the same bone-chilling experience to their audiences.

Yes, even today, nearly 51 years after its release, watching this film is as nightmarish and unsettling as it was for moviegoers in 1974. See for yourselves just how effective it remains, if you are mentally prepared for it.

Just remember, the decision is yours alone. At ynet, we hereby disclaim all responsibility, and nothing above should be considered a viewing recommendation or an encouragement of any kind. Did we cover ourselves properly? Good. Good luck. You will need it.