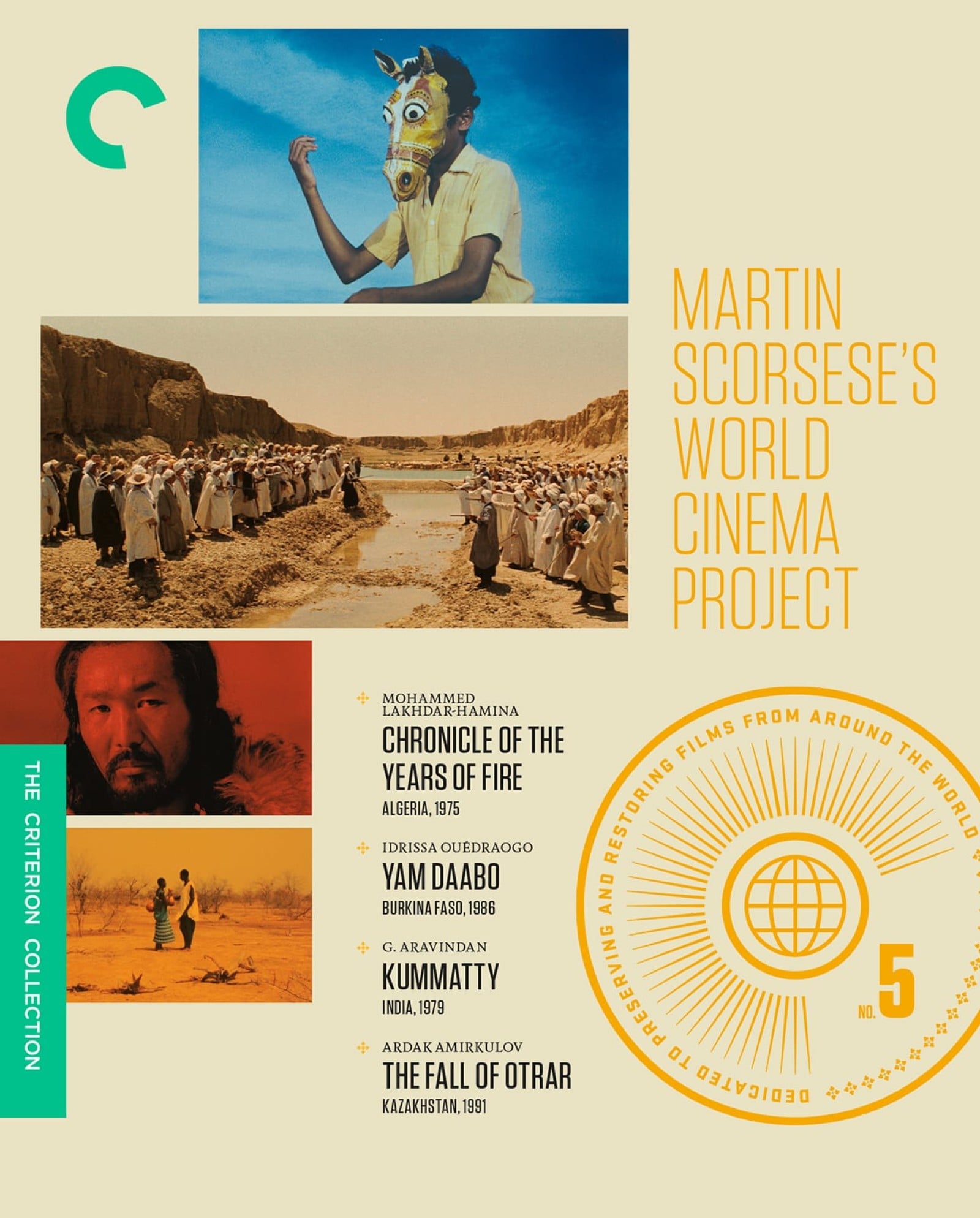

The Criterion Collection’s latest bundle of films restored by Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project is bookended by two of the largest spectacles in the series to date: Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina’s Palme d’or-winning Chronicle of the Years of Fire, which reorients the visual language of a David Lean epic around the perspective of a colonized people, and Ardak Amirkulov’s The Fall of Otrar, which was made off and on for a period of years during the collapse of the Soviet Union.

The Criterion Collection’s latest bundle of films restored by Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project is bookended by two of the largest spectacles in the series to date: Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina’s Palme d’or-winning Chronicle of the Years of Fire, which reorients the visual language of a David Lean epic around the perspective of a colonized people, and Ardak Amirkulov’s The Fall of Otrar, which was made off and on for a period of years during the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Beginning in the lead-up to the Second World War and carrying through to the period of the postwar Algerian independence movement and eventual war, Chronicle of the Years of Fire centers its vast canvas on Ahmed (Yorgo Voyagis), who uproots his family from a drought-ravaged village to Algiers, where he becomes radicalized by the exploitation he suffers at the hands of French colonists. Lakhdar-Hamina arranges gorgeous but bleak vistas of arid landscapes before slowly shifting into staged recreations of guerilla warfare or French reprisals that focus less on the action itself than the aftermath of bodies littering streets. Galvanizing in its depiction of tribal conflict giving way to solidarity against a common enemy, the 1975 film nonetheless never loses sight of the immense cost of gaining one’s freedom.

The Fall of Otrar details the story of one of Genghis Khan’s most brutal conquests: the eradication of the Khwarazmian Empire after its shah recklessly executed the Mongol’s envoys. Co-written by maverick Russian filmmaker Aleksei German and his wife and frequent collaborator, Svetlana Karmalita, Amirkulov’s 1991 film shares many of that director’s stylistic and thematic preoccupations, as evidenced by the swooning, dreamy long takes and garishly sensual evocation of the filth and fury of pre-modern life.

For all the immensity of its production design and its impressively mounted battle scenes, the film often conveys an intense claustrophobia befitting the siege campaign that brought the walled city of Otrar to its knees. It’s also one of the greatest movies ever made about irreconcilable culture clash, of what happens when two civilizations have such radically different values that neither can comprehend the other and sees annihilation as the only logical response.

Sandwiched between these colossal works are two comparatively shorter features: Idrissa Ouédraogo’s 1987 debut, Yam Daabo, and G. Aravindan’s Kummatty, from 1979. Yam Daabo’s title translates to “The Choice,” a brutal and multivalent irony considering the hardships on display, which range from economic desperation to the false promise of urban prosperity for rural transplants to the violently possessive tug of war by two suitors for the same woman.

Ouédraogo is anti-lyrical in his approach, presenting this harsh land in stark cuts and minimally moving shots and filling the soundtrack with the sounds of hoes tilling rocky soil and the occasional snap of gunfire. And yet, the film also takes care to point out the grace that people extend to each other even at the height of conflict. A handshake between fathers dissipates the tensions raised by their competing teenage sons, and elsewhere, a show of humanity from a seemingly lost soul toward an old friend inspires the latter to return to a home he abandoned.

The fabulistic Kummatty follows a Pied Piper-esque magician (Ambalappuzha Ravunni) who charms local children into obedience and devotion. Against expansive landscape shots of the mountainous, tropical southern Indian state of Kerala, Aravindan’s film gradually induces a sense of the uncanny using in-camera techniques. Opening the aperture a few extra stops in daytime scenes, Aravindan and cinematographer Shaji N. Karun overexpose the images to make the sky appear almost blindingly bright and hyperreal. And when the sorcerer starts weaving his magic, quick edits are used to convey the effect of his transfiguring spellcraft. Sidestepping any simple moral for the sake of a more ambiguous, folkloric tale of a radical journey back to where one started, the film is as beguiling and relaxing as it is unnerving.

Despite their lack of relation to one another, the films in Criterion’s box set share certain thematic and stylistic parallels. All four boast stellar vistas, while the magic-realist tone of Kummatty makes for easy programming alongside the almost alien atmosphere of The Fall of Otrar. The more intimate drama of perseverance and struggle seen in Yam Daabo mirrors much of the same motivating hardship besetting the central family of Chronicle of the Years of Fire before that film expands into something much larger.

Image/Sound

All four films receive transfers from new 4K restorations (overseen by the World Cinema Project in collaboration with the Cineteca di Bologna), and given the sorry state of preservation that some of these movies were in previously, the results are astounding. The streaks of verdant color in Kummatty and Yam Daabo pop against the swaths of brown and yellow soil and sand. Both the sepia-tinted monochrome and full-color scenes of The Fall of Otrar look crisp with stable contrast and clarity well into the background of deep-focus compositions. Chronicle of the Years of Fire looks best of all, with the image depth so clear that you can make out the sand cakes into the lines of faces and the stained browns and yellows on well-worn desert clothing.

The soundtracks are of more variable quality, all seemingly endemic to the conditions in which they were recorded. (A tinniness can be heard in The Fall of Otrar when characters’ voices echo in cavernous rooms.) Still, there are no discernible issues with the discs’ reproduction of these tracks, and in all cases dialogue, music, and sound effects are well balanced.

Extras

Each of the films comes with an introduction from Martin Scorsese, who recounts his memories of seeing them for the first time and of the World Cinema Project’s often fraught efforts to restore them. A documentary about the making of The Fall of Otrar amid the collapse of the Soviet Union features interviews with director Ardak Amirkulov, actor Tungyshbai Dzhamankulov, production designer Umirzak Shmano, and film journalist Gulnara Abikeyeva, while the other films are supplemented with interviews with film scholars (and, in the case of Kummatty, its filmmaker’s son, Ramu Aravindan). These interviews all provide helpful social context for the times and places in which the movies were made, as well as deeper dives into the oeuvres of their respective filmmakers. An accompanying booklet contains essays on the films by critics and historians Joseph Fahim, Chrystel Oloukoï, Ratik Asokan, and Kent Jones.

Overall

The Criterion Collection offers four neglected classics their much-deserved moment in the sun with the latest iteration of its World Cinema Project series.

Score:

Cast: Yorgo Voyagis, Larbi Zekkal, Cheikh Nourredine, Hassan El-Hassani, Leila Shenna, Aoua Guiraud, Moussa Bologo, Ousmane Sawadogo, Fatimata Ouédraogo, Assita Ouédraogo, Ambalappuzha Ramunni, Ashok Unnikrishnan, Sivasankaran, Kothara Gopalkrishnan, Vilasini, Dokhdurbek Kydyraliyev, Tungyshbai Dzhamankulov, Bolot Beyshenaliyev, Abdurashid Makhsudov Director: Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina, Idrissa Ouédraogo,G. Aravindan, Ardak Amirkulov Screenwriter: Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina, Tewfik Fares, Rachid Boudjedra, Idrissa Ouédraogo,G. Aravindan, Kavalam Narayana Panicker, Ardak Amirkulov, Aleksei German, Svetlana Karmalita, Ardak Amirkulov Distributor: The Criterion Collection Running Time: 502 min Rating: NR Year: 1975 – 1991 Release Date: January 20, 2026 Buy: Video

If you can, please consider supporting Slant Magazine.

Since 2001, we’ve brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.