In 2004, two Aussie filmmakers not only took Robert Redford’s Sundance Film Festival by storm, but the horror industry at large. That year, James Wan and Leigh Whannell stood outside Park City’s Egyptian Theatre, braving the winter’s biting cold while their nasty, tear-your-guts-out feature debut played to audiences for the first time. That film, the spark that’d ignite a massive franchise sensation for Lionsgate, is, of course, Saw.

At this year’s Sundance, Wan and Whannell returned to Utah’s ski resort hub to pay homage not only to their film’s anniversary, but also to Sundance’s final year in Park City before the impending move to Boulder, Colorado. Saw was programmed as part of a “Park City Legacy” slate, since a fateful Sundance Midnight premiere launched one of the buzziest, bloodiest intellectual properties in 2000s horror history.

Speaking exclusively to Bloody Disgusting, Whannell reflects: “I was standing outside the Egyptian last night, and they’re not showing movies there this year. I felt melancholy about that, because that was where Saw premiered. It feels like the end of an era for Sundance, and a full circle for us, just to be back here. Things were happening to us at that age, faster than we could move, and we were going along with it.”

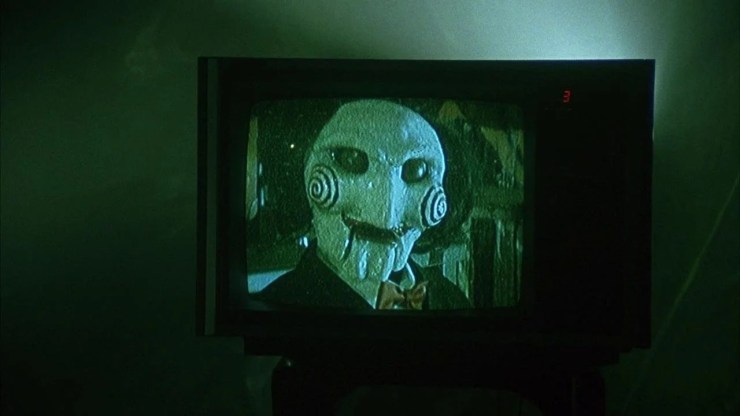

The solemnity in his voice is understood. Saw’s triumphant return to Sundance 22 years later puts it among countless other monumental breakouts. Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs, Ryan Coogler’s Fruitvale Station, and Mary Harron’s American Psycho are in league with a trike-peddling puppet with blood-red, swirly cheeks (who also returned to Sundance).

Leigh Whannell in Saw

It’s a full-circle moment for Wan, who made a promise to himself about attending film festivals.

“Leigh and I had this philosophy, back when we were in Australia, that we wouldn’t go to a particular festival unless we had a movie showing. Sundance was our first mainstream festival. I’ve always said, ‘I’m not going to come back to Sundance until I come back with a movie.’ And, well, I’ve never had a chance to come back with another movie until now.”

A lot was, in fact, happening to Wan and Whannell — but they were savvier than most rookie creators. According to Business Insider, they turned down a $5 million offer from Lionsgate before striking a deal with the studio where they’d forgo an advance, pay Lionsgate an “18%-20%” distribution fee, and pocket the rest. Notably, Saw grossed $104 million worldwide on a $1 million budget. These boys knew they had a hit on their hands, but to the extent that the franchise exploded? No one could predict.

Part of the pomp and circumstance around Sundance releases is the reception. Sometimes filmmakers humbly accept standing ovations; other times they’re verbally accosted outside theaters by furious attendees (like Lucky McKee after The Woman). When I asked Wan and Whannell what post-screening reactions stood out to them, the Aquaman director lit up and, quite playfully (very good-natured), recalled a close-to-home memory:

“Bloody Disgusting shit on it! [Saw] was reviewed by Brad Miska’s brother, and I have held Brad to the fucking fire over that. When he got around to watching [Saw], he told his brother, ‘What the fuck are you talking about? Did we not watch the same movie?’ [Brad] said that his brother watched [Saw] when he was really drunk that night, at the premiere. [His brother] was like, ‘I don’t know what movie I just watched.’ You can quote me on that one.”

Bloody Disgusting atoned for its sins when its managing editor Meagan Navarro ranked it among the best horror movies of the 2000s. (Editors note: Brad Miska, who left the company last year after ceding site operations to EIC John Squires in 2021, reviewed the film favorably.)

However, critiques are merely one post-release inevitability for any filmmaker. What’s more important is the almighty dollar. Ticket sales dictate a film’s longevity and future possibilities. Saw’s performance was so prolific that it didn’t just spawn a franchise that’s still beating John Kramer’s dead (or alive) corpse, with entries pouring out of his cracked skull like a graveyard piñata. Saw was the new “It” thing, horror’s subgenre du jour. Studios clamored to acquire or produce their Saw lookalike—your Grotesque (2009) or Captivity (2007)—but, as is typically true, no copycats could dethrone Jigsaw.

Shawnee Smith as Amanda in Saw.

Still, Wan and Whannell had to watch as less-than-valiant mimicry turned the public sour on Saw-esque movies. Thus, the term “Torture Porn” became both a subgenre classification and a low-blow critique to generalize these gore-heavy, plot-thin mutilation parades. The “Splat Pack” era, as Wan remembers, although he shooed away the “Torture Porn” phrase (rightfully so, given how Saw reached far beyond mindless gratuity). Imitation is the sincerest form of flatter after all, and per Wan, “We were honored that people felt that our movie meant something and that they wanted to imitate it. [Horror] movies don’t look like that anymore, but I’m sure it’ll come back. Like fashion, it’s cyclical.”

Whannell is a little more introspective about their influence over the Horrorsphere. “It was cool that we were like the tip of the spear in this movement, this trend—and that was a great thing for two people who really wanted to be in the film business.” Saw was a pop-culture phenomenon, thanks in part to Tobin Bell‘s iconic role as John Kramer, and also to everyone’s favorite cackling dolly, Billy the Puppet.

“There were Saw references in The Simpsons, South Park, The Sopranos … It was pretty awesome to penetrate pop culture in that way.”

As we all know, much of the Saw franchise was produced without Wan or Whannell’s involvement despite being the concept’s masterminds. “I didn’t do the sequels because I felt I had already made the movie I wanted to make,” Wan confirms. “Leigh was going to produce, and ultimately, he was going to write [Saw II] … at least one of us has a creative voice that is going to at least shepherd the next one or two movies.” But that would only last Saw II and Saw III, as we all know. After that? Whannell reminisces about how Saw kept evolving without their guidance. “James and I had this strange, surreal experience once a year, driving down the street and seeing a billboard for this thing that we created in Melbourne when we were starving ex-film students, and now it’s out in the world.”

‘It wasn’t for a lack of money either,” Wan interjects, regarding his declining to participate in any sequels despite Lionsgate’s financial sweeteners. “I’m still crying about it,” a fourth voice chimes in from over my shoulder. “Put this in the article, ‘A single tier fell down the face of their agent, Scott Henderson,’” Whannell insists with a grin.

Whannell confirmed that although he lasted longer than Wan, apprehension was abound. “The true story is, I followed James’s lead at first. I didn’t want to be involved either.” Apparently, [Lionsgate] came back to Whannell once they had a writer and begged him to “pretty please get involved.” With proper incentives, Whannell penned his two sequels, but by Saw III, he’d reached his limitations. “I was like, ‘Yeah, I think I’m done here. I can’t think of any more ways to kill someone with a power drill.’”

So what did Whannell do? Put a stake through Jigsaw’s heart.

“I killed Jigsaw. I was like, ‘This is pretty definitive.‘ Which [Lionsgate] regrets to this day. If the producers could go back in time, they wouldn’t be killing Hitler, they’d be convincing me not to kill Jigsaw.”

With overnight attention came trepidation and mild paranoia. Whannell continues, “We had this fear of like, we didn’t want Saw to be our epitaph.” They didn’t want Saw to be their legacy because that would mean nothing else connected with audiences. “So when we did Insidious, it was a big sigh of relief … because luckily we were not one-hit-wonders.” In Whannell’s words, they avoided the curse of Dexys Midnight Runners. “[All] they get asked about is ‘Come On Eileen,’ yet they had other songs.” Thankfully, as the years went by and both filmmakers bolstered their resumes, success became a perennial occurrence.

Although there was one unfortunate side-effect of their meteoric rise to superstardom, in Whannell’s opinion: Dead Silence.

When I asked Whannell what advice he’d give to his pre-Saw self, the wide-eyed Australian lad about to rewrite horror history, he said, “I would go back and tell myself, ‘Hey, slow down. Wait until [Saw] comes out and then make some choices.’” When asked if that was a slight on Dead Silence, he confirmed directly, “I’ve been complaining about Dead Silence for 20 years, I’m not going to stop.”

At this point, the interview turned chaotic in a completely on-brand and delightful way. Wan and Whannell are poster boys for best-friend dynamics, with energetic jesting and mutually committed bits.

I tried my best, as a Dead Silence defender, to turn Whannell’s disdain. Alas, he insists, “I think my final words … My daughter’s going to grasp my hand, and [say], ‘I love you, Dad.’ Then I’m going to respond like, ‘Me too. But that fucking puppet movie, man. What the hell were they thinking?’”

Wan adds fuel to Ravens Fair’s fire by calling Dead Silence Whannell’s Rosebud, to which the goaded scribe retorts with a smile, “Yeah, Rosebud. Except no one will know what it means because I’ll be like, ‘Shh.’”

For what it’s worth, Mr. Whannell, I’m still a ride-or-die Mary Shaw advocate.

Dead Silence’s Billy might be a one-and-done scarer, but Saw’s Billy is a creepy phenomenon. What’s even funnier? He almost didn’t exist.

Whannell recalls pitching Wan Amanda Young’s “Reverse Bear Trap” sequence. He describes their working partnership as putting “two ingredients together,” bouncing ideas off each other from opposite perspectives. In this case, Wan’s intuition was spot-on. According to Whannell, after he detailed Amanda’s grueling test, Wan calmly added, “That’s cool. If we put a creepy doll in there, it’ll be perfect.” Wan’s social media handle is @creepypuppet, so duh.

“I didn’t, at the time, think the creepy doll was necessary,” Whannel confesses. It would be like, I felt like me calling Orson Welles and being like, ‘At the end of the movie they find [Rosebud], and it says Rosebud, and the whole movie is tied up in this beautiful bow.” And then Orson was like, “But then what if they had like a judo fight after that?” As we know, Billy the Puppet has endured countless failed sequels and still sells merchandise at a substantial clip, so it’s evident who was right. “James is clearly the smartest of the two of us. And so now, when he tells me what to do, I do it.”

Wan and Whannell’s Sundance trip is a bittersweet sendoff, yet it represents a milestone victory lap for the artists. What these two have accomplished since Saw‘s initial emergence is nothing short of a miracle. “You would walk down the street, and we would hear strangers talking about our film, not knowing that we were involved,” Whannell fondly remembers. Fame hasn’t corrupted these genuinely excellent humans, who still exude the passion and vitality of fresh-out-of-school babyfaces. Without James Wan, without Leigh Whannell, the horror landscape would’ve veered into territories unknown. Twice, if you count how Wan’s The Conjuring pulled theatrical horror back into the marketable haunted house era. Their ideas aren’t run-of-the-mill—they generate nightmares and lay groundworks for multi-entry stories that people ravenously crave.

But if there’s one constant in their lives, it’s a very special friend who is the real celebrity of their trio. States Wan, gesturing at the remote-controlled Billy wedged between them on a generic Sheraton Inn couch, “The kickstarter of our career, really. We wouldn’t be here if it weren’t for this guy.”

Related: James Wan and Leigh Whannell tease Saw future plans.