A composite image shows a grilled eel restaurant in Ganghwa County, Incheon, registered as the headquarters of an agency founded by actor Cha Eun-woo’s mother. Korea Times photo by Kang Ye-jin

It takes about an hour by car from downtown Seoul to reach the Ganghwa Island, where a grilled eel restaurant flanked by rice paddies can be found.

This remote location is the registered address of D ANY, the alleged shell company for Cha Eun-woo, whose real name is Lee Dong-min. The company is a so-called “single-artist agency,” where Cha’s mother is listed as the CEO and Cha is the sole affiliated artist.

Located in Bureun-myeon, Ganghwa County, Incheon, the eel restaurant operated for five years starting in 2020. It is currently empty, as the business moved to Seoul in the second half of last year.

The interior of the grilled eel restaurant formerly operated by actor Cha Eun-woo’s parents in Ganghwa County, Incheon, on Jan. 28 / Korea Times pho to by Kang Ye-jin

Last week, the doors were wide open, allowing reporters from the Hankook Ilbo to inspect the interior. The area was so secluded that the barking of a dog at a nearby guesthouse was virtually the only noise.

While the space seemed suitable for a grilled eel restaurant, it was an awkward location from which to support the activities of an entertainment star. There was nothing in the building that looked like a practice studio or a business office.

“I knew it was ‘Cha Eun-woo’s eel house,’ but I never imagined it was registered as an entertainment agency,” said a man who operates another restaurant nearby. “Is it because they set up an agency in such a remote place, is that why they are suspected of being a shell company?”

The National Tax Service (NTS) notified Cha of a tax penalty in the 20 billion won range ($13.7 million) because investigators determined “D ANY” was a shell company with no reason to exist other than for tax avoidance.

Since his debut in February 2016, Cha has been active as an artist under the agency Fantagio. The NTS declared that Cha’s activities could be fully supported through Fantagio alone and that he received “improper benefits” by inserting the legal entity “D ANY” in between, taking advantage of the corporate tax rate of 26.4 percent, rather than the individual tax rate that can be as high as 49.5 percent.

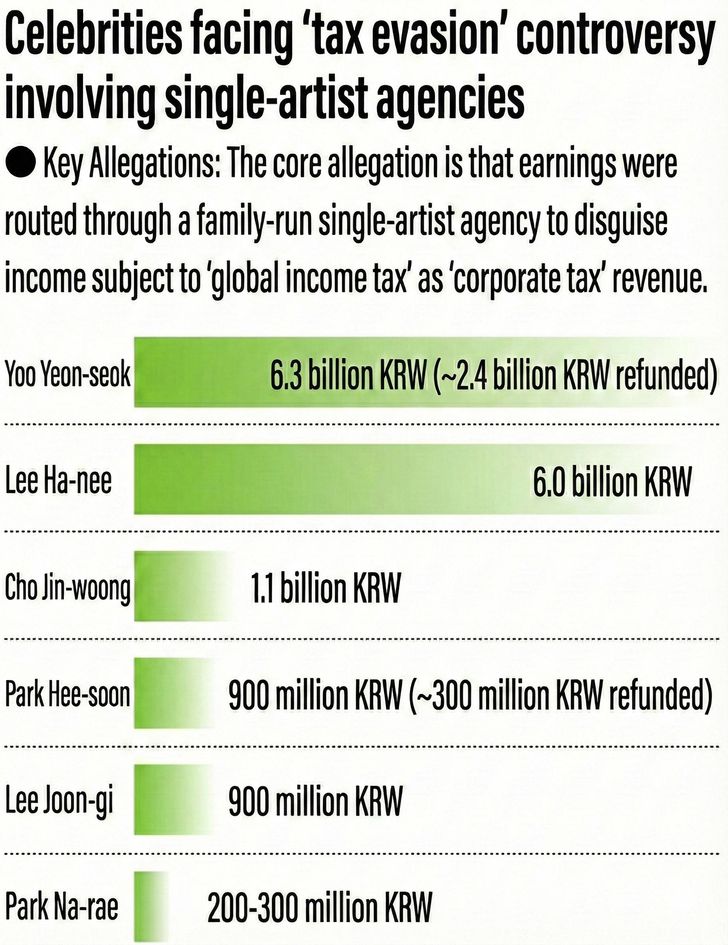

The chart generated by artificial intelligence shows a list of celebrities who face ‘tax evasion’ controversy involving single-artist agencies and the scale of income subject to global income tax as corporate tax revenue. Courtesy of Hankook Ilbo

Cha faces the highest penalty amount among Korean celebrities, but he is not alone: A significant number of entertainers face similar allegations. The practice has spread in recent years.

To understand why, the Hankook Ilbo interviewed 15 people, including NTS officials, tax experts and entertainment industry insiders. The consensus was that high-income earners were increasingly using corporations as a tax-saving tool. Analysts suggest that tax evasion controversies have become frequent due to the unique nature of the entertainment industry, including skyrocketing celebrity fees and low barriers for establishing corporations.

‘Too Crude’: Why authorities suspect deliberate fraud

The logic of the Seoul Regional Tax Office’s Investigation Bureau 4 is straightforward — Cha diverted his personal earnings through a family-run shell company.

“Corporations and individuals are ‘separate legal entities.’ However, if a corporation receives tax benefits without performing any actual corporate function, authorities will pierce the corporate veil and tax the income as if it belongs to the individual,” explained You Jin-woo, CEO of Tax & Realty.

Many experts point out that the intent behind Cha’s alleged evasion seems particularly deliberate.

One key indicator is that the company changed its structure from a joint stock company to a limited liability company (LLC). Unlike joint stock companies, LLCs are exempt from external audits and public disclosure requirements.

“Switching to a closed company structure like an LLC can be interpreted as aggressive tax avoidance,” said Yoo Ho-rim, a professor at the Graduate School of Science in Taxation at Kangnam University.

The grilled eel restaurant in Ganghwa-gun, Incheon, on Jan. 28. This location serves as the registered headquarters for Cha’s single-artist agency. Korea Times photo by Yun Gi-hun

Another red flag is the relocation of the corporate headquarters to Ganghwa.

“In districts like Gangnam and Mapo, where entertainment agencies are concentrated, local offices conduct rigorous on-site inspections on registration. They likely chose a region with almost no agencies to evade this scrutiny,” said the head of a singer-focused agency.

It also appears to be a strategy for real estate speculation. Corporations located in Ganghwa are exempt from heavy acquisition taxes on real estate because the area is classified as a ‘growth management zone’ under the Seoul Metropolitan Area Readjustment Planning Act. The business registry for D ANY, officially listed as a ‘popular culture planning business,’ also includes rental business.

The NTS reportedly imposed a penalty of 8.2 billion won on Fantagio as well, concluding that the agency processed false tax invoices for the corporation. The allegations against Cha reportedly surfaced during an initial investigation into Fantagio.

“There are strong indications that the agency knew about Cha’s tax evasion,” said a tax accountant with extensive experience in corporate tax. “But the scheme was too unsophisticated to look like the involvement of a large management company.”

The high-stakes gamble of incorporation

Both Cha and Fantagio released statements addressing the allegations. While the wording differed, both insisted that the NTS findings are not 100 percent factual. Indeed, the mere act of establishing a corporation is not illegal. The key question is what the corporation actually did and to what extent.

Measuring the “economic substance” of a corporation is rarely a black-and-white issue.

“The specific role a corporation plays has long been a controversial subject,” said an NTS official. “We must look at whether it functioned by weighing various criteria comprehensively.”

Since the income split is determined by a private contract between the corporation and the entertainer, the arrangement remains open to interpretation.

“Even if the NTS decides that the income is excessive compared to the corporation’s function, the taxpayer can claim the corporation deserves that share of the earnings,” another NTS official explained.

Frequently, the penalty amounts are adjusted during appeals to the Tax Tribunal or through administrative lawsuits. They can even be revised during the NTS’s internal pre-taxation review.

In 2023, the NTS processed 2,132 such reviews and accepted the taxpayer’s claim in 438 cases, or about 20 percent of the time. In monetary terms, out of the 1.969 trillion won originally marked for collection, 939 billion won was canceled after review— nearly half the total penalty amount.

Tax industry insiders say high-income earners consider this worth a shot.

“If tax saving through a corporation works, you save a fortune. If it doesn’t, you just fight it out through the appeals process,” said a tax accountant based in Seoul.

Pedestrians walk past Fantagio headquarters in Samseong-dong, Seoul, on Jan. 27. Korea Times photo by Kang Ye-jin

Structural flaws fuels tax evasion

While celebrity tax scandals attract intense attention due to public interest, the attempt to evade taxes is not confined to top entertainers. As more individuals generate revenue through personal branding, the number of corporations similar to Cha’s solo agency have surged.

Methods of evasion are diverse. They include converting personal income into corporate revenue, listing family members or acquaintances as employees to pay them fake salaries, processing private spending as business expenses and using corporate funds as personal piggy banks.

However, the four entertainment agency CEOs interviewed by Hankook Ilbo pointed to characteristics unique to the industry that make it especially susceptible to tax evasion.

One major factor is the explosive rise in celebrity fees. With the advent of streaming services such as Netflix and the global influence of the Korean wave, the market value of top stars has jumped tenfold in recent years.

Income polarization also drives incorporation. As wealth concentrates among a handful of top stars, incomes for the rest have dropped sharply. To retain every cent of their earnings, many lower-tier artists are establishing corporations.

“To survive in this industry, artists have to secure opportunities the agency can’t get for them. Reliance on agencies has decreased,” one agency CEO said. “If they have to split that hard-earned income, they have little choice but to move quickly to set up a corporation.”

Strict limits on expense deductions further fuels the trend. Unlike manufacturing, artists providing human services have few areas where they can claim business costs.

“Entertainers often got caught trying to save on taxes by claiming maximum expenses. While things like plastic surgery are for their career, proving direct relevance to their work is incredibly tricky,” explained Shin Yu-han, a tax accountant. “Eventually, celebrities moved away from making ambiguous expense claims altogether, and establishing corporations emerged as the new tax-saving trend.”

A view of the building in Cheongdam-dong, Seoul, where the grilled eel restaurant managed by Cha’s parents is located / Korea Times photo by Kang Ye-jin

Low barriers for establishing agencies also contributes. With minimal effort, anyone can set up a family-run single-artist agency. Under current law, a business license is granted to anyone with two years of experience in the industry and a registered office space.

“It’s not an atmosphere where regulators meticulously check if someone is qualified to run an agency,” a CEO from the Korea Entertainment Producer’s Association said. Another head of a label based in Seoul added that using a “nominee owner” — someone who lends their name as a figurehead — is common.

Agencies are powerless to stop it because they depend heavily on their top talent.

“When a successful artist demands to renew a contract through their new single-artist agency, we have no choice,” said a CEO with 25 years of experience. “Fantagio, as a KOSDAQ-listed company, would see its stock price plunge if it lost its flagship star, Cha Eun-woo. I suspect the company cooperated even if it believed Cha’s family-run agency was being used for tax evasion.”

This article from the Hankook Ilbo, the sister publication of The Korea Times, is translated by a generative AI system and edited by The Korea Times.