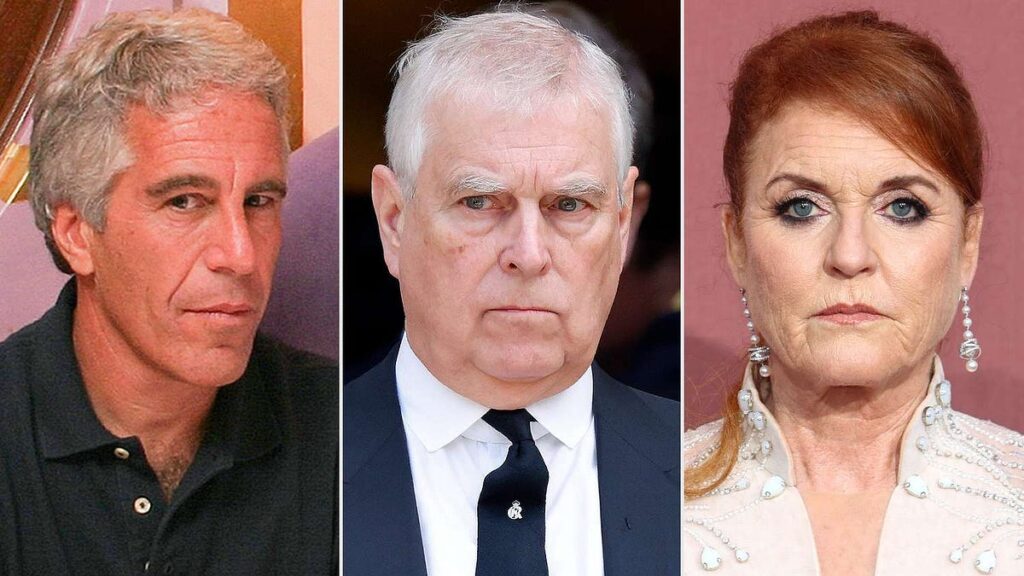

The latest round of attention on the Epstein documents has revived a thorny question: what, exactly, are institutions supposed to do when prominent figures are publicly connected to someone like Jeffrey Epstein?

Some of Britain’s front pages of Britain’s showing an image of Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor included in the Epstein files, seen on Feb. 1, 2026.

Some of Britain’s front pages of Britain’s showing an image of Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor included in the Epstein files, seen on Feb. 1, 2026.

What’s becoming clearer is that most institutions don’t actually have a roadmap for this scenario at all. There is no consistent protocol for reputational contamination—no clear threshold at which proximity to bad actors becomes disqualifying.

Instead, responses appear to hinge on something far more subjective: perceived fallout.

Across royal households, charities, and affiliated organizations, the trigger for action has not been anyone’s connection to Epstein itself, but rather its exposure. It isn’t the relationship itself that causes apologies, suspensions, or removals; it’s being caught in public with it, sometimes years later, and only when documents or discrepancies become impossible to manage.

Though a similar version of this dynamic is undoubtedly playing out across the globe, the British royal ecosystem offers a particularly instructive case study.

Take Sarah Ferguson, whose longstanding ties to Epstein were not new information. They were documented, reported, and broadly understood well before this most recent wave of scrutiny. Yet the consequences have arrived in stages—that is, not all at once.

Last autumn, Ferguson was removed as patron of several charities—after just one email emerged in which she apologized for publicly disavowing Epstein.

At the time, the moves were framed as tactful but necessary. Ferguson’s own representative told media: “The Duchess [as she still was in September 2025] spoke of her regret about her association with Epstein many years ago, and as they have always been her first thoughts are with his victims. Like many people, she was taken in by his lies.”

The spokesperson went on, “As soon as she was aware of the extent of the allegations against him, she not only cut off contact but condemned him publicly, to the extent that he then threatened to sue her for defamation for associating him with paedophilia. She does not resile from anything she said then. This email was sent in the context of advice the Duchess was given to try to assuage Epstein and his threats.”

Only now, with more explicit and uncomfortable details back in circulation, has Ferguson’s own charity announced the suspension of its operations (and even that is framed as being just “for the foreseeable future”). The newly released files reveal that her correspondence with Epstein continued long after his 2008 conviction, extending into at least 2011. The escalation of consequence here tracks external pressure, not her actual behavior.

A similar pattern appears with the former Prince Andrew.

Despite his public disgrace and removal from royal duties, Andrew remained in residence at Royal Lodge (with the added perk of a “peppercorn” rent) for years. The process of ending his tenancy reportedly began last year, yet he has stayed put, both physically and symbolically, long after his institutional role had ended.

Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor rides a horse in Windsor Great Park, near Royal Lodge in Windsor, on February 2, 2026.

Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor rides a horse in Windsor Great Park, near Royal Lodge in Windsor, on February 2, 2026.

New reports this week suggest a sudden shift. Andrew is said to have vacated the 30-room Royal Lodge abruptly, in the early hours on Monday, even though renovations on his new residence, Marsh Farm, have not yet been completed. He is expected to reside temporarily at Wood Farm on the Sandringham estate in Norfolk in the interim. What was once painted as, regrettably, impossible turned out to be pretty achievable after all!

The difference, in my view, was pressure. Accountability doesn’t seem to grow on trees in the House of Windsor.

And yet, when moments like this arrive, the line institutions reliably return to is that “the victims should be the focus.”

In response to the newest batch of Epstein-related documents, Buckingham Palace has directed media back to a statement published on October 30th, 2025. (“That guidance stands,” now seems to be the refrain at Buckingham Palace as well as Kensington):

“His Majesty has today initiated a formal process to remove the Style, Titles and Honours of Prince Andrew.

Prince Andrew will now be known as Andrew Mountbatten Windsor. His lease on Royal Lodge has, to date, provided him with legal protection to continue in residence. Formal notice has now been served to surrender the lease and he will move to alternative private accommodation. These censures are deemed necessary, notwithstanding the fact that he continues to deny the allegations against him.

Their Majesties wish to make clear that their thoughts and utmost sympathies have been, and will remain with, the victims and survivors of any and all forms of abuse.”

This framing is, on its face, unobjectionable. Of course victims matter. Of course they should be centered.

But the invocation of victims in discussions about Andrew Mountbatten Windsor also functions as a convenient endpoint. It discourages further examination of how his connection to Epstein and potential victims was allowed to exist—and continue past the point that a principal royal once claimed—in the first place.

You cannot have victims without perpetrators. And you cannot have perpetrators operating at this scale without systems that enabled, insulated, or ignored them.

Expressions of sympathy do not explain why associations were tolerated for so long, why responses arrived only after perceived fallout intensified, or why remedies once described as impossible suddenly became administratively achievable. Centering victims should not preclude interrogating harmful structures.

Taken together, these cases suggest that royal institutions, and the organizations orbiting them, are not responding to ethical thresholds so much as reputational ones. The question being answered in the wake of the Epstein files’ release is not, “What should happen when association becomes known?” but “What can no longer be defended?”

Earlier this week, at the World Governments Summit in Dubai, Prince Edward, Duke of Edinburgh, became the first member of the British royal family to publicly reference the Epstein files. In widely circulated reporting, his remarks were summarized as a “breaking of silence,” or else a reminder to “remember the victims.” It is a framing that aligns neatly with the Palace’s existing position.

But the fuller context of his comments complicates that narrative.

Prince Edward, Duke of Edinburgh, at the World Governments Summit in Dubai on Feb. 3rd, 2026.

Prince Edward, Duke of Edinburgh, at the World Governments Summit in Dubai on Feb. 3rd, 2026.

Speaking onstage with CNN journalist Eleni Giokos, Edward first appeared to dismiss the topic’s relevance to the room, noting that the audience had come to discuss education and “solving the future.” Only then did he pivot, adding in a response that mirrored the question but not much else, that it was important to remember the victims, and that there were “a lot of victims in all this.”

That opening qualifier has largely been omitted from coverage. Instead, we zero in on the portion of his answer that signals concern…while still sidestepping more uncomfortable questions about responsibility, delay, and prior tolerance.

Again, Epstein’s victims do not exist in isolation. They are produced by actions, protected by prejudices and silences, and often failed by systems that hesitate to intervene until the cost of inaction becomes too high. The Epstein files do not simply tell us who knew or did what, and when. They expose how consistently institutions struggle, or even refuse, to act unless and until any perceived fallout outweighs reputational loyalty.

The reckoning, when it comes, is rarely proactive. It arrives late, unevenly, and only after the narrative has already escaped institutional control.