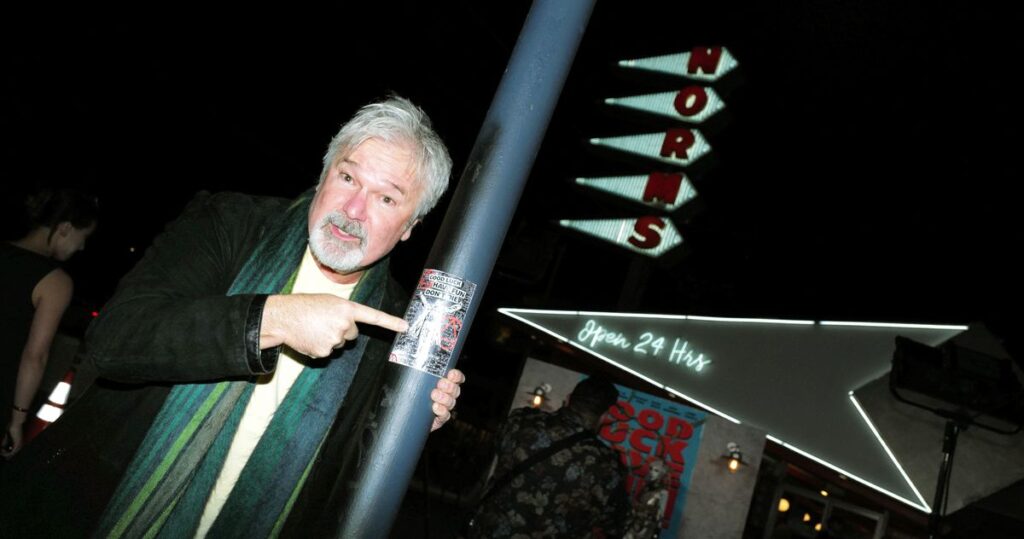

Photo: Eric Charbonneau/Briarcliff Entertainment via Getty Images

In the opening moments of the gonzo sci-fi action-adventure comedy Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die, a wild-eyed character played by Sam Rockwell bursts into a Los Angeles–area diner with a bizarre hostage demand. Six randomly selected patrons must help him save humanity from marauding artificial intelligence or everyone in the restaurant dies via suicide vest. Claiming to have beamed in Terminator style from the dystopian, not-too-distant future, Rockwell’s twitchy, rubber-faced Man From the Future (that’s his name according to the credits) possesses an uncanny familiarity with all the diners at Norms; he says he’s already been to this very restaurant 117 times trying to stop the apocalypse. Soon, he’s rounded up six ill-prepared and mostly disbelieving randos (Zazie Beetz, Michael Peña, Haley Lu Richardson, and Juno Temple among them), who embark on what could be a suicide mission where they will encounter forces both wondrous and baffling: facing off against a legion of social-media-addicted Gen-Alpha quasi zombies, biomorphic mountains of murderous toys, and a brontosaurus-size cat creature with even more disproportionately massive genitals (not to mention a bottomless appetite for human flesh).

Premiering at Austin’s Fantastic Fest in September, Good Luck won over critics and dazzled audiences who didn’t seem entirely sure what to make of its rollicking genre mash-up and sheer fuck-it joie de vivre. But the film’s director, Gore Verbinski, can also be understood to have beamed in from a different dimension. The erstwhile Hollywood rainmaker behind Johnny Depp’s multibillion-dollar grossing Pirates of the Caribbean franchise, the 2012 smash remake of Japanese avant-horror exercise The Ring, and the animated hit Rango (for which Verbinski collected a 2012 Academy Award for Best Animated Feature) hasn’t released a movie since 2017, the critical and commercial disappointment A Cure for Wellness. The unkind take is that he has been in directors’ jail since that time. The more generous view holds that Verbinski decided to step back from Hollywood’s gigantic, creaking content conveyor belt to follow his bliss.

What remains incontrovertible: After a string of blockbusters — and infamously pushing back against Disney chief executive Michael Eisner, who thought Depp’s Keith Richards–esque Captain Jack Sparrow was “ruining” the Mouse House’s Pirates IP during filming on Pirates I — Verbinski’s box-office run of success came to a skidding halt with 2013’s The Lone Ranger. That $215 million would-be tentpole infuriated critics, alienated viewers and slank from the multiplex after grossing $260 million: an era-defining flop. Since then, the director will tell you he has been moving without the ball, struggling valiantly to set up a suite of projects including a George R.R. Martin adaptation and “high concept” animated musical.

Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die is Verbinski’s first indie movie. He actively pieced together its slight $23 million production budget and distribution via “studio of last resort” Briarcliff Entertainment in a hands-on manner that would be inconceivable to most filmmakers belonging to the three-commas club. The 61-year-old Tennessean admits a certain recalcitrance toward the current requirements for studio-movie blockbusterdom: “I don’t know that the stuff I’m interested in doing necessarily makes it through a green-light committee.”

There’s a crazy, let’s-throw-everything-against-the-wall-and-see-what-sticks quality to this movie. How did you gravitate toward Matthew Robinson’s script?

Isn’t the world screaming the answer? I read it in 2020 and just was really enraptured by it. Then we spent two years working on it because AI has changed in our lives so rapidly from his original 2017 draft. We worked quite a bit on Sam Rockwell’s character’s backstory. But it just felt like it needed to be now. I was working on an animated musical that was taking a long time, a couple of other projects that were taking a long time. And there was a sense of, This needs to come out tomorrow.

Hollywood moves at a slow pace. It tends to be hard to make a movie addressing current events because movies spend years in development while the Zeitgeist moves on. Yet this one lands squarely in the cultural moment with an encroaching fear of the AI singularity and school shootings and the scourge of social media. How did you decide to hit those targets?

When I first started working in this industry, the old-time producers would say, “Whatever you do, don’t mix genres.” Well, that’s all we fucking do! Mix the tone, you know? Our little psychotic opera has five narratives. This sort of a Captain Beefheart [narrative]: Sam Rockwell climbs out of a dumpster and enters Norm’s [diner] strapped with explosives, saying he’s from the future. I’m a huge fan of Dog Day Afternoon. Sal and Sonny are the worst bank robbers. They are not capable. I guess I’m a fan of that —capable is boring. So then we have this collection of misfits sent to save the future. The future is so fucked. It sent us Sam Rockwell, not Arnold Schwarzenegger. And he’s not at the San Diego Navy SEAL academy. It’s Norms.

I don’t know your films to be explicitly taking on societal ills in this way. What made you want to be topical in your filmmaking right now?

I would say the first three Pirates movies are about the post-modern western, corporate greed, the East India Trading Company. There’s no place for honest pirates in a dishonest world. There’s always a bit of medicine buried in the icing of the cake. You don’t need to know it’s there. I think what you are responding to is, with this one, it’s not buried. The medicine is right there. It’s a contemporary narrative. We’re already growing ears on the backs of rats.

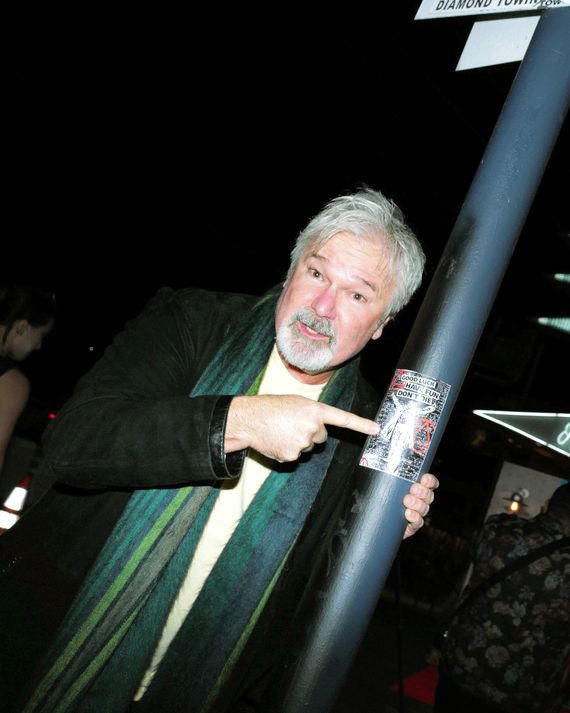

Photo: Briarcliff Entertainment

This is your first indie film. I understand you had a direct hand in putting together financing from various European partners and bringing Good Luck to Briarcliff, which is a scrappy Hollywood upstart. Talk me through how this project came together on a financing level and where you found the money for it.

Every major studio had passed on the script. And in the spirit of Repo Man from 1984 — a movie that smells like nobody asked permission to make — we knew it was going to have to be willed into existence. [Producer] Denise Chamian and our casting director just said, “Let’s just put out a casting call.” I started meeting with Haley Lu and Zazie and Michael and we built this ensemble cast around Sam. Then this company Constantine heard about us, read the script, saw our cast, and heard the budget. Then they said, “Can you do it for half?” So we had to do the foreign-financing thing where money comes and it falls away and then you’re there and then you’re not there; you’re lurching toward production.

We got the L.A. tax incentive; we tried to make it here. Couldn’t hit that number. Tried to make it in Vancouver, chased that tax incentive. Tried to make it in Winnipeg. We ended up in South Africa to shoot the movie. That’s the state of our industry. Tom Ortenberg at Briarcliff still believes in the theatrical experience. So after we had made the film, we partnered with him. They’ve been great — scrappy but great. And we went to Fantastic Fest and Beyond Fest and found some champions for the movie. We’re sort of finding the audience that we made the movie for.

You’ve done some movies based on iconic IP. You’ve excelled at IP. But this is gravitating away from that. Why?

I’ve never approached any of the IP I’ve done without the sense of, How do I corrupt that in some way? I always feel like, If you’re not a little mischievous, you’re blind to the absurdity of life. I try to apply that whether it’s a $200 million movie or a $15 million movie. When you are making it for this number, you’re not going to take notes from an algorithm.

Were you personally involved in those negotiations to pull together a budget? Or did you leave that to producing partners?

No. I’ve never been more involved in more aspects of a production. There’s no “team” at Constantine or Briarcliff. There’s just five people and every person is doing 27 things. In order to get the movie made, you’ve got to go meet the German financiers. I’m trying to explain this movie to them and why they should invest in it. I’d rather not have to do that. It’s not my jam.

Let me ask you a hard question. The last movie you had in theaters was A Cure for Wellness in 2017. You said you have been working on an animated musical that is taking a long time. But I’m sure readers are going to be like, Where has Gore been? So, where have you been?

I’ve been working every day. We’ve got a great script called Sandkings based on a George R.R. Martin short story. We’re developing a very strange adaptation of The Gashlycrumb Tinies, an Edward Gorey narrative. There’s three or four original scripts that I’m pushing forward. I don’t know that the stuff I’m interested in doing necessarily makes it through a green-light committee. If you’re saying where have I been? I’ve been right here, duking it out.

I don’t mean to be an asshole. It just seemed like you put together gigantic blockbuster after gigantic blockbuster. You won an Oscar for Rango. And then after The Lone Ranger there was a change of momentum. Am I right in thinking that? And does it presage what you are talking about in terms of doing what you are interested in as a filmmaker versus what the studios want from you?

I think you are talking about the financials. You are talking about profits. I feel like I’m still the same person sweating and tinkering. Sometimes they blow up and sometimes they don’t. When I first heard somebody wanted to make The Lone Ranger, I said, “We should do it from Tonto’s perspective. We should do the Sancho Panza version.” I was never going to do it straight.

Again, I’m not interested in capable. I need to find a way into it — that’s what I’ve always done. If you look at anything I’ve done, successful or not, the approach is always the same. At the end of the day you have to answer the question, Why must I tell this story? If you can’t answer that, you might as well sell real estate for a living. It’s just too freaking hard to make a movie.

I think the answer to your question is from a banker standpoint: Those movies made money and this one didn’t. There was never a thought about making money on any of the successes. In fact, it was the opposite. On the first Pirates, they [Disney] were so scared. The second one, they’re like, Just keep doing what you’re doing. That’s when I got nervous — when we’re not scaring them anymore. Does that answer your question? Sometimes they blow up. You might as well be asking about fads. You might as well be asking about bell-bottoms. I’m just making pants.

Looking at your track record as a blockbuster filmmaker, I never understood you as a reflexive contrarian.

I’ve had crew print T-shirts that say “Relentless.” I took that as a compliment. Because mediocrity is just nipping at your heels from the outset of an endeavor. The enemy is not the studio. The enemy is not the executives or the fear. The enemy is if you don’t go out and claw and scratch every day. It’s just going to be okay. It’s just going to be meh.

This movie was, in a sense, harder than any other movie but also more rewarding. Everybody had that sneaky feeling like you were getting away with something. It’s that punk-rock attitude.