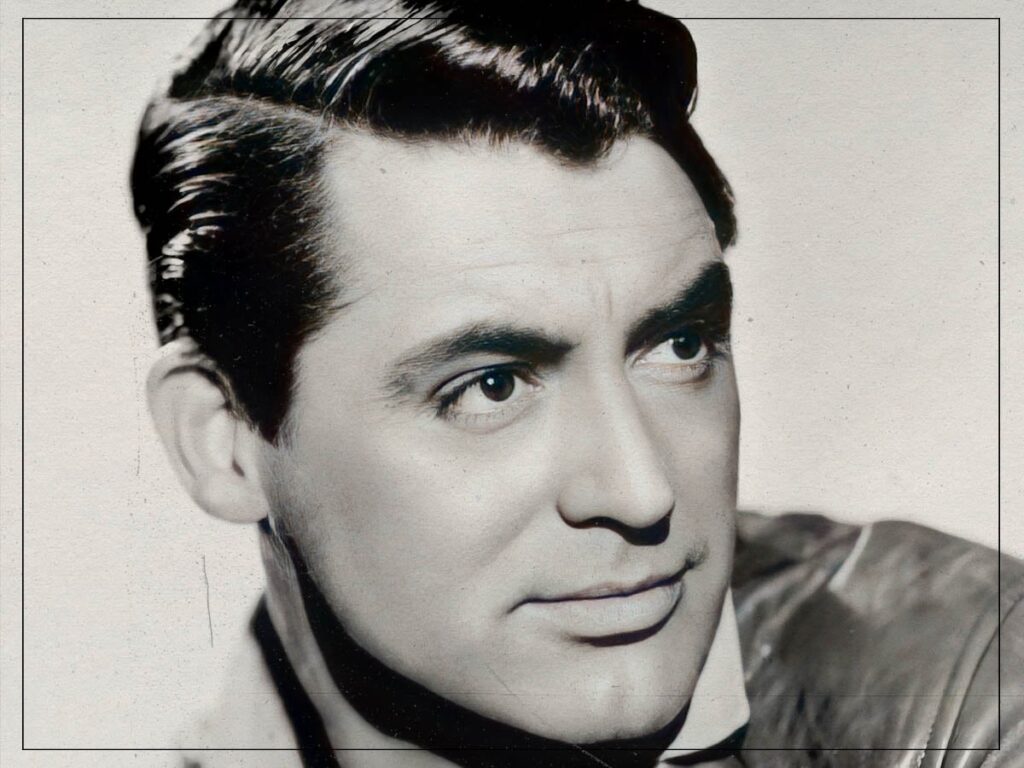

(Credits: Far Out / Wikimedia)

Fri 13 February 2026 21:15, UK

History will always remember Cary Grant as one of cinema’s most iconic leading men, but there’s every chance that his career could have gone a completely different way had his offer to buy his way out of a movie after the first day of shooting been approved.

Although it took him less than a decade to crack the A-list after making his big-screen bow in 1932’s This Is The Night, the way the old studio system worked ensured that he’d appeared in dozens of pictures by the time he finally managed to stand out from the crowd and establish himself as a leading man.

The period between 1938 and 1940 was instrumental to that success, with Grant pulling his weight in critical, commercial, and awards season favourites like Bringing Up Baby, His Girl Friday, Only Angels Have Wings, and The Philadelphia Story, all of which have become certified ‘Golden Age’ classics.

However, the year before saw the release of The Awful Truth, which can be pinpointed as the catalyst behind his subsequent rise. It was his 29th feature, but it was the most important by far, with Leo McCarey’s screwball comedy cleaning up at the box office and earning six Academy Award nominations, including ‘Best Picture’, with McCarey taking home the ‘Best Director’ prize.

Every aspect of the screen persona that made Grant such an era-defining star was on full display for the first time, and the suave, debonair romantic foil with a twinkle in his eye would become his stock-in-trade from then on. And to think, he was initially so resistant to McCarey’s methods that he wanted out.

The filmmaker wasn’t a big fan of rehearsals, and he adopted an improvisational approach to developing the script and shooting the picture, which didn’t sit well with an actor who was as uncomfortable as they were unproven in working that way. After day one, things reached a head, and he tried to bail. He wasn’t alone, though, with co-star Irene Dunn feeling the exact same way.

“At the end of the first day, Irene was crying; she didn’t know what kind of a part she was playing,” third-billed Ralph Bellamy recalled. “Cary said, ‘Let me out of this, and I’ll do another picture for nothing.’” When that fell on deaf ears, he decided to go straight to the top when the first week of principal photography was over.

Grant sent an eight-page memo to Columbia Pictures chief Harry Cohn titled, ‘What’s Wrong With This Picture’, extensively outlining his issues with how McCarey was handling The Awful Truth. He also offered to pay $5,000 to be extricated from his contract, in exchange for making his next film for the studio free of charge, which was rejected.

When McCarey caught wind of his star’s subterfuge, he offered Cohn an additional $5,000 to get rid of him, which was denied. In the end, he stayed the course, and looking at how integral it was in cementing the idealised version of Cary Grant that audiences would know and love for decades, if he’d gotten his way and weaselled his way out of The Awful Truth, things could have turned out markedly different.