If you’re a millennial woman, America’s Next Top Model may have been your first experience of appointment TV. The show, which ran for 10 years from 2003, was an early reality juggernaut and made a household name of the supermodel Tyra Banks, its creator and host. At its peak, Top Model drew more than 100 million viewers globally, and left a niche but indelible impact on culture. “Smize”, meaning to “smile with your eyes”, is in the Collins dictionary, while Banks’ infamous tirade (“We were all rooting for you!”) at an unruly model still circulates as a meme.

With its high-concept photoshoots and extreme makeovers, Top Model was ahead of its time in manufacturing viral moments. Today, however, the exacting critiques and body-shaming makes for deeply uncomfortable viewing, as gen Zers bingeing the show through the pandemic have pointed out. This latter-day reckoning is the peg for Netflix’s three-part docuseries, Reality Check: Inside America’s Next Top Model.

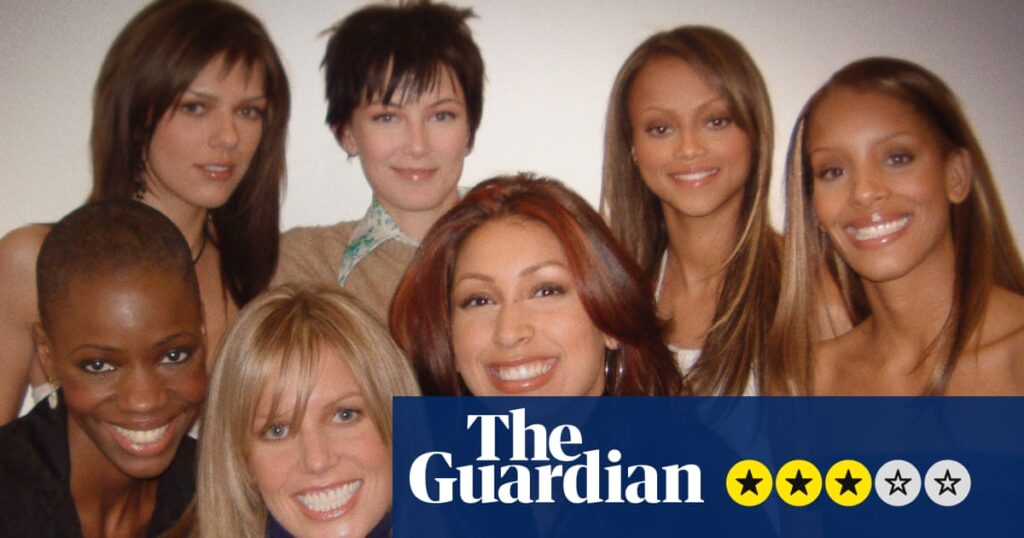

The series boasts remarkable access: Banks, the catwalk coach J Alexander, creative director Jay Manuel, photographer Nigel Barker and executive producer Ken Mok all sit down to interviews, along with dozens of former contestants. It suffers, however, from the usual Netflix issues: it is overlong, unevenly paced and frenetically edited. What could have been a powerful 90-minute film instead spans three hours, yet the zippy, TikTok-y treatment robs it of impact.

Banks presents herself as a trailblazer determined to democratise modelling and diversify fashion, but Reality Check shows that Top Model was just as intent on upholding the toxic status quo. Women were weighed on camera, their bodies criticised. Giselle, an African-Latina woman Banks proudly says she fought to cast, was ridiculed for having a “wide ass”. “That’s how I talk to myself, to this day,” she winces, decades later. In a safari-themed photoshoot, a woman deemed to be bigger was made to pose as an elephant.

Today, Top Model’s “challenges” seem like humiliation rituals. One contestant, Dani, was pressured to have a gap closed in her teeth. Another, Dionne, was asked to pose with a bullet wound in her head; her mother had been shot by an ex-lover and left paralysed. “I thought it was a coincidence,” she says.

Mok airily admits that particular shoot was “a mistake”, as a “celebration of violence”, though he seems impervious to individual suffering. Banks, meanwhile, demurs from addressing storylines and production (“not my territory”).

Many contestants came from deprivation, and blame Banks for leading them to believe Top Model was their ticket out. Instead, most found the show worked against them. Surprise, surprise: the fashion industry wasn’t swayed by Top Model’s OTT, increasingly tasteless photoshoots, showing models posing as homeless, murder victims or ethnicities other than their own.

Though the judges display more contrition than Mok and Banks, all involved are eager to agree the series falls short of 2026 standards. What Reality Check makes clear, however – but fails to emphasise enough – is that many contestants expressed distress at the time, and were manipulated or pressured into participating.

Most disturbing is contestant Shandi’s account of the models’ trip to Milan. After a drunken hot-tub party with some local men they’d met on a photoshoot, Shandi had sex with one in the shower, then went to bed with him, trailed the whole time by camera crews. Neither Shandi nor the documentary explicitly refers to this as sexual assault, but the original Top Model footage suggests she was too drunk to consent. Shandi tearfully tells the documentary that she’d drunk two bottles of wine and was “blacked out for a lot of it”: “I just knew sex was happening, and then I passed out.” And not only did production not intervene, “it all got filmed”.

Mok’s defence is that Top Model was filmed “as a documentary, and we told the girls that from day one”, adding that the scene was significantly “scaled back” in post-production. “For good or bad, that was one of the most memorable moments in Top Model.” Shandi says her distressed demands to leave the production were denied, and she was only given a phone to call her boyfriend on the condition that it was filmed and recorded.

The crew apologised afterwards, Shandi says: “They just knew that this isn’t right.” Banks’ response, meanwhile, was to take all the women out for some girl talk on the terrazza, holding court about relationship mistakes and “primal desires” as the camera lingered on agonised Shandi. The episode aired with the title “The Girl Who Cheated”.

Banks, it must be said, comes across as a real piece of work, passing the buck while bragging about her knack for identifying talent and what audiences want. She even blames Top Model’s extremes on viewers: “You guys were demanding it.” When Banks professes to feel grateful for having been pushed to reflect and evolve, it comes across not just as false, but obliquely threatening: may the rest of us be as gracious when we’re called out, “because that day will come”, she says, ominously.

Reality Check is right to conclude on the former contestants, all much happier and healthier-looking than their Top Model days, and powerfully clear-eyed about the mark the show left on them. But it does them a disservice by persistently framing Top Model as a product of its time, and criticism as coming only from woke gen Z. For a show about beauty, Top Model was always ugly – but Reality Check’s conclusions are only skin deep.