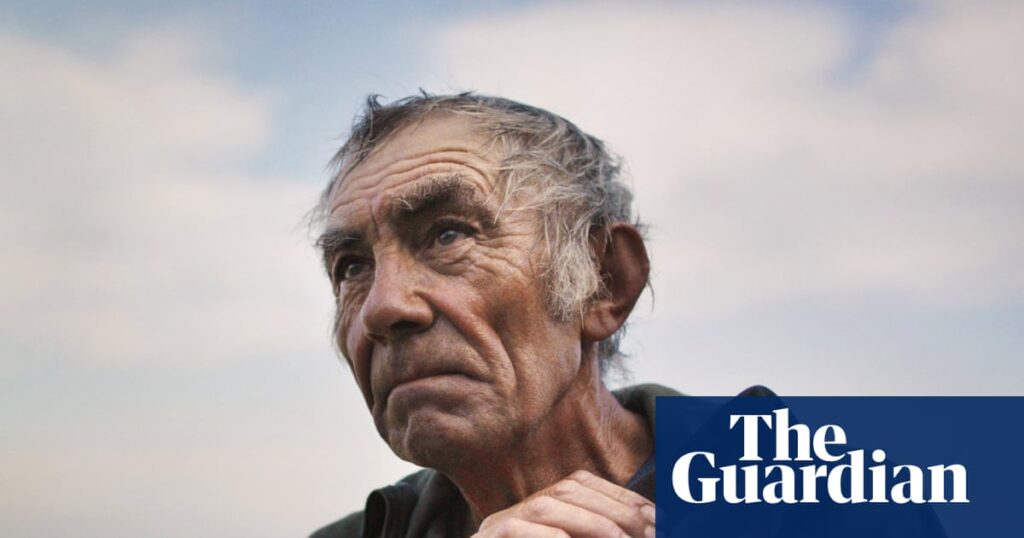

One of the best horror scenes this year arrives in a documentary about French pastoralism. It’s pitch-black out on a Pyrenean mountainside. Wagnerian lightning illuminates the ridges and the rain sheeting down. Bells clank in darkness as the sheep flee en masse to the other side of the col. Yves, the shepherd in charge, faces down this bewilderment, trying to perceive the threat: “Are those eyes?”

The Shepherd and the Bear, directed by Max Keegan, is part of a new breed of films with a heightened sympathy for country matters. Surveying the wind-ruffled pastures, lingering in battered cabins, it’s a highly cinematic depiction of the conflict in the Pyrenees provoked by the reintroduction of the brown bear. Much past rural cinema made hay from insisting we beware of the locals: Deliverance’s vicious hicks, The Wicker Man’s wily pagans, Hot Fuzz’s Barbour-jacketed cabal for the “greater good”. But the new school rides with the locals like Keegan’s film taps their knowledge and tells us what they’ve known all along: that it’s nature that’s truly scary.

With the Ariège département ruralists in semi-revolt against laws that stop them culling the bears, and Yves struggling to find a successor, The Shepherd and the Bear is typical of European neo-rural cinema in focusing on collisions and conflicts of tradition and modernity in the 21st-century countryside.

New countryside alliances … The Eight Mountains. Photograph: Alberto Novelli

It’s a windfarm vetoed by French arrivistes that causes meltdown in Spanish Galicia in 2022’s crime thriller The Beasts, while Catalonia’s peach groves are to be uprooted for solar panels in the delicate drama Alcarràs, from the same year. The town and country divide quietly underpinned the story of a Turin prodigal son’s return to Italy’s Aosta valley in the epic The Eight Mountains (2022). And 2020 documentary The Truffle Hunters depicted the last stand of Piedmont’s geriatric mushroom men.

The Beasts and The Eight Mountains both deal explicitly with a growing phenomenon: the return of urbanites to the land, a cohort the French call les néoruraux. This partly accounts for cinema’s sharpened familiarity with countryside concerns, with some film-makers even personally spanning the divide. Francis Lee, who directed 2017’s God’s Own Country – about a tryst between a Yorkshire sheep farmer and a Romanian labourer – grew up in that milieu. Louise Courvoisier, director of last year’s tearaway cheese-making drama Holy Cow, splits her time between film-making and working on her family’s farm in the Jura region.

Tearaway cheesemakers … Holy Cow. Photograph: Laurent Le Crabe/Zeitgeist Films

Even if neo-rural films aren’t directed by countryfolk, they no longer feel like works made by hapless outsiders who would, were they in a film themselves, be liable to face the wrong end of an aggressive banjo solo. Hope Dickson Leach’s The Levelling (2017) lays out the suffocating pressures on British farmers with sobering grace; in France, 2023’s Super Bourrés (a kind of Gallic Superbad about home-brewing teens) and Junkyard Dog (a sort of Gallic Withnail and I about a dysfunctional friendship), show strong familiarity with the scrappy, hard-partying ennui outside the cities. Grímur Hákonarson’s Rams (2015) – which makes an Old Testament feud of a pair of sheep-farming brothers – does something similar for Iceland.

There have been earthy, intimate rural films in earlier decades: Peter Hall’s generational village chronicle Akenfield (1974); or Manon des Sources (1986), about Provençal water conflicts; or Béla Tarr’s Sátántangó (1994), more than seven hours of unrelenting misery in the Hungarian mud. One thing that marks out the recent flurry, though, is an artisanal reverence for rural producers that, in the era of Vittles foodie culture, is quite distinct from past miserabilism. From Yves’ herding in The Shepherd and the Bear, to the tomato and peach cultivators in The Beasts and Alcarràs, and the quest for the perfect comté in Holy Cow, it’s striking how many of the neo-rural brigade find heroism in supplying the horn of plenty.

The old ways still persist in some quarters – this is the countryside after all. Hoary demonisation of queer rural folk is still an easy win, cropping up lately in the scrumpy-making sociopathic child-snatchers in 2024’s Speak No Evil, or the “very country” ensemble of village freaks all played by Rory Kinnear in 2022’s Men. The acceleration of folk-horror in the UK from its beginnings in the 1960s to the glut of recent years has been something to behold; the recent documentary The Last Sacrifice explains it as the product of a particular British insularity that also puts up impenetrable hedgerows within our isles themselves – resulting in the dark fascination of the urban imagination with what lies beyond.

Old ways … The Last Sacrifice. Photograph: Anti-Worlds

It’s striking that the continent produces virtually no folk-horror. Perhaps this is due to a different, less mythologised, more pragmatic relationship with the land (the UK still imports nearly half of its food, compared with 20% in France). But the tensions – whether between rural old-timers and urban wantaways, traditional methods and modern eco directives – are there.

And neo-rural cinema is there to witness that violence can erupt around them: in The Beasts, the enmity between worn-down locals and the idealistic newcomer leads to some very tense games of dominoes and then a sudden murder. A bear is finally shot in a neighbouring region in The Shepherd and the Bear, and Yves and other locals mutter dark approval. With such pent-up passions in the air, it’s easy to see how country life begat folk-horror – but digging into the raw reality allows us to see the furrows go so much deeper.

The Shepherd and the Bear is released in UK cinemas on 6 February.