American supermodel Bella Hadid takes to Instagram every few years to share a behind-the-scenes look at living with chronic illness.

In one slideshow from September 2025, she’s seen getting a variety of treatments at a boutique medical facility. In another from August 2023, Hadid shows herself with an intravenous catheter connected to her arm.

In that post’s caption, she claims to have suffered from Lyme disease for more than 100 days — as well as “almost 15 years of invisible suffering.”

That post has garnered about three million likes and 19,000 comments. Many users expressed support. One commented, “Who of you also suffers from chronic Lyme? What treatments do you do?”

Lyme disease is a medically recognized infection that can cause pain, fatigue and muscle aches. But many celebrities — including Hadid, American singer Justin Timberlake and Canadian singer Justin Bieber — who claim they have Lyme appear, on a closer look, to be describing chronic Lyme disease, a condition that isn’t recognized by conventional medicine.

American model Bella Hadid has spoken publicly about her struggles living with chronic illness and her ongoing treatments. (Yolanda Hadid/Instagram, Bella Hadid/Instagram)

American model Bella Hadid has spoken publicly about her struggles living with chronic illness and her ongoing treatments. (Yolanda Hadid/Instagram, Bella Hadid/Instagram)

It’s a controversial term used by some alternative practitioners to describe pain, fatigue and neurological symptoms they attribute to a persistent Lyme infection. Often, patients have never tested positive through a regulator-approved Lyme disease test.

Despite the shaky validity, identifying otherwise-unexplainable symptoms as chronic Lyme can seem like a path toward getting better, Dr. Paul Auwaerter, a professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, told CBC News.

“They are looking for answers to something that many times they get short shrift from their regular physicians or from consultants.”

But experts warn that the world of private testing and treatment is largely unregulated — and can carry serious risk.

How Lyme disease works

Lyme disease is caused by Borrelia burgdorferi, a bacterium that’s transmitted through the bite of infected blacklegged ticks. Symptoms can include a rash, fever, fatigue and joint aches.

The disease is on the rise globally, including in Canada. There were 5,809 reported cases of Lyme disease in this country in 2024, according to the Public Health Agency of Canada. It has been trending upward nationally since 2009, according to Health Canada — in part due to climate change and a greater awareness among the public and doctors.

The majority of people who contract Lyme are cured with early antibiotic treatment, Auwaerter said. If left untreated, the disease can become serious and spread to the joints, heart and nervous system.

Where some of the confusion may come from, experts say, is that some people continue to have debilitating symptoms after treatment for confirmed Lyme, including fatigue, cognitive difficulties and muscle and joint pain. Doctors call this post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome (PTLDS). They don’t have a clear explanation for what causes it, and as a result, treatment for it isn’t well charted, Auwaerter said.

This undated photo provided by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows a blacklegged tick, which is also known as a deer tick. (CDC/The Associated Press)

This undated photo provided by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows a blacklegged tick, which is also known as a deer tick. (CDC/The Associated Press)

“As you might detect from the name, ‘syndrome’ means we don’t quite understand why it occurs in people,” he said.

“That’s still a very significant area of research to try to understand that, much like long COVID,” he said, referring to the longer-term illness that affects some people months after being infected with COVID-19.

Sometimes, Lyme, chronic Lyme and PTLDS are used interchangeably. But experts told CBC News they aren’t the same. With chronic Lyme, the belief is that the Lyme bacteria stays in a person’s body even after antibiotics, requiring constant treatment.

Most medical experts say there’s no evidence backing this theory.

“Many of us that study Lyme disease don’t think after initial antibiotic treatment that there is still bacteria harboured there that would respond to antibiotics,” Auwaerter said.

And this belief can be harmful, because people are often advised to spend large sums of money on treatments, said Andrea Love, an immunologist and the executive director of the American Lyme Disease Foundation.

“There is a very lucrative wellness industry that centres around Lyme disease and this idea of this persistent infection.… They get really rich off of exploiting vulnerable people.”

Misleading tests and treatments

In Canada, testing for Lyme disease is a two-step process that includes screening the blood for antibodies produced by the immune system in response to the infection, plus additional confirmatory testing. Tests cannot detect Lyme bacteria itself.

The tests are Health Canada-approved and are an important part of the diagnostic process. But they aren’t perfect, Auwaerter said.

There is an initial period where antibodies don’t detect the infection, he said. And sometimes, these tests can come back positive even years after the initial infection, even though it isn’t necessarily still active.

“It becomes a struggle where we don’t have a clear black-and-white test that says, ‘Do you have Lyme disease or not,’” he said.

Meanwhile, people in Canada can get private tests done through alternative practitioners who send them to out-of-country labs, some of which claim to be superior to regulator-approved tests.

“They claim that they’re providing you a more accurate, more sensitive test for Lyme disease,” Love said.

Some clinics offer urine-based tests, something she called “wholly inappropriate.”

“It’s not going to detect those bacteria,” she said.

WATCH | Lyme disease experts say misinformation about Lyme is fuelling a dubious industry:

Why do so many celebrities have Lyme disease?

Celebrity claims are fuelling confusion about the risks of Lyme disease. For The National, CBC’s senior health reporter Christine Birak investigates what’s really behind the boom in high-profile cases and uncovers a big-money industry profiting off chronic illness. [Correction: A previous version of this video included images of American dog ticks. It’s been updated to include images of blacklegged ticks.]

Some private clinics also offer treatments ranging from hyperthermia therapy to stem cell therapy to plasma exchanges. These can be dangerous because they haven’t been proven to help treat Lyme disease, making them unnecessarily risky. The same goes for long-term antibiotic use.

And since the idea of chronic Lyme gives people the impression that ongoing treatments are necessary, it could encourage people to pursue “a lifetime of getting high-intensity therapies,” said University of Alberta infectious diseases specialist Dr. Lynora Saxinger.

It can also mean that some people don’t get the chance to be diagnosed with a medical condition they do have. In 2021, Auwaerter co-authored a 2021 study looking at 1,261 people referred for a suspected case of Lyme disease. Researchers found that 84 per cent of them had no findings of the actual disease.

In fact, most had a new or pre-existing disorder causing their symptoms, most often anxiety and depression, as well as fibromyalgia, but in rare cases even multiple sclerosis and cancer.

‘Selling hope’

In one case, an attempt to treat chronic Lyme became life-threatening.

Feile O’Connell from Tofino, B.C. told CBC News she almost died after undergoing an unproven treatment in Mexico.

The 30-year-old said she’d been struggling to get help for ongoing severe fatigue and pain for years. She hasn’t been able to work, and said the health-care system has let her down.

A doctor tested her for Lyme disease, but the result was negative. She said she kept trying to get answers from doctors, but only got the runaround.

Feile O’Connell says she nearly died after one of the treatments she received at Lyme Mexico, a clinic that claims to specialize in treating Lyme. (Submitted by Clodagh O’Connell)

Feile O’Connell says she nearly died after one of the treatments she received at Lyme Mexico, a clinic that claims to specialize in treating Lyme. (Submitted by Clodagh O’Connell)

“I can’t even count how many specialists I saw,” she told CBC News. “They would say, ‘I can’t help you. This is all that I can do, so go back to your family doctor,’ which I didn’t have at the time… I kept being pushed back to square one.”

As her symptoms worsened, she turned to a naturopath, paying for out-of-country blood tests that came back positive for Lyme disease, she said. (The Canadian medical system only recognizes Health Canada-approved test results.)

“I felt validated for the first time,” O’Connell said.

After trying alternative treatments in Canada for months, in the summer of 2024 she ended up at Lyme Mexico, a clinic that claims to specialize in treating Lyme disease, run by Omar Morales. All in, she said her treatment and accommodations cost over $40,000.

“He’s selling hope,” she said. “All we want is to get better and he has the path.”

Omar Morales runs Lyme Mexico in Puerto Vallarta. It offers a variety of treatments, many of which aren’t proven to treat Lyme disease. (Lyme Mexico Clinic/YouTube)

Omar Morales runs Lyme Mexico in Puerto Vallarta. It offers a variety of treatments, many of which aren’t proven to treat Lyme disease. (Lyme Mexico Clinic/YouTube)

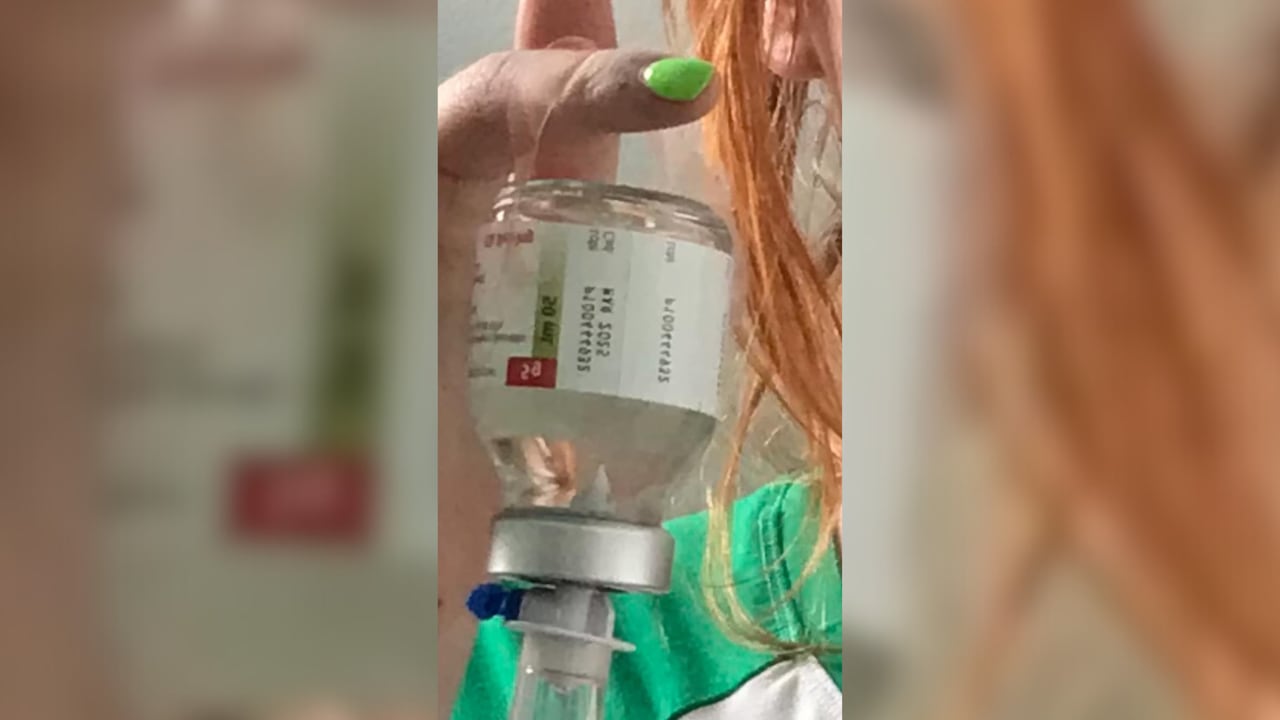

At Lyme Mexico, she said she received an intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) treatment, where the antibodies from donated plasma are used mainly to strengthen the immune system. She said this made her violently ill.

O’Connell said she ended up in a local intensive care unit with sepsis, a life-threatening condition caused by an infection. She later contacted the pharmaceutical company with the lot number of the product.

“We conclude that these units have been subject to a fraudulent transaction and there is a high probability that the unit administered to the patient has been falsified/manipulated,” CSL Behring stated in a letter to O’Connell.

“We emphasize that genuine Higlobin batches that have been supplied through the distribution chain authorized by CSL Behring are safe and effective,” it said.

“If I could take it all back, I would, 100 per cent. I would never recommend for anybody to go there,” O’Connell said.

The photo O’Connell took while undergoing IVIg treatment that helped her track down the manufacturer of the product. (Submitted by Feile O’Connell)

The photo O’Connell took while undergoing IVIg treatment that helped her track down the manufacturer of the product. (Submitted by Feile O’Connell)

In an email to CBC News, Lyme Mexico’s patient director Sandy Rodriguez said the clinic could not comment on individual cases due to privacy regulations.

“Lyme Mexico is a licensed medical facility, and all treatments are provided by qualified physicians under established safety and informed-consent protocols,” she wrote.

Asked for proof of those qualifications, the clinic wouldn’t provide them.

Several other patients who spoke to CBC News said they were satisfied with the care they received.

WATCH | This B.C. woman says treatment attempt at Lyme Mexico clinic became life-threatening:

She says she nearly died after an unproven Lyme treatment in Mexico

30-year-old Feile O’Connell says she almost died after getting an unproven treatment at a clinic that claims to specialize in treating Lyme disease in Puerto Vallarta, Mexico.Unmet health-care needs

Time and again, what’s driving people toward the chronic Lyme industry is a lack of effective, long-term health care, said Saxinger.

“The thinner the medical system gets stretched, the less likely someone… is going to be able to get significant time from the routine medical system,” she said.

There’s also a need for more research into chronic illnesses to help those suffering, Auwaerter said.

“This has been quite an underfunded area for many years,” he said.

O’Connell, the woman from B.C., said she still has ongoing symptoms. She said she is still pursuing treatment for chronic Lyme disease, and is working with a naturopath who’s prescribed her antibiotics.

She said what would make a difference for patients struggling with chronic illness is more empathy and understanding from physicians.

“People are really cast aside when they have these mysterious chronic illnesses,” she said, “and they’re just left to fend for themselves.”