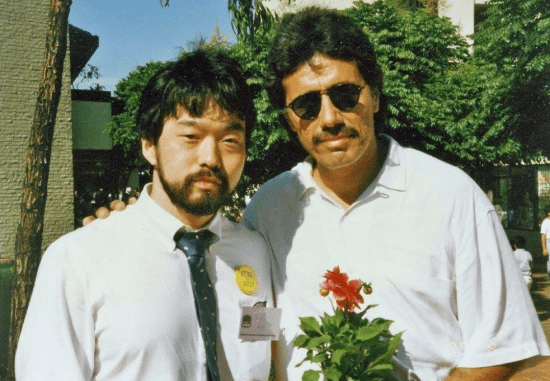

Guy Aoki of NCRR and actor Edward James Olmos

Guy Aoki of NCRR and actor Edward James Olmos

By GUY AOKI

People tend to forget that even after we lobbied Congress to pass HR 442 in 1987 and Reagan signed it on Aug. 10, 1988, we still had problems getting the concentration camp survivors paid.

On July 25, 1989, of the bill’s $1.2 billion, the House Appropriations Committee only allocated $50 million to be spent for fiscal year 1990. At that rate, only those older than 86 would receive restitution, and an estimated 200 internees had died every month since the bill was passed. So NCRR wanted to organize a big protest to draw attention to the cause and pressure Congress to do the right thing.

At a committee meeting, we ran through the usual celebrity names (Martin Sheen, Edward Asner, Jane Fonda, Casey Kasem, etc.). Then someone suggested Edward James Olmos. The Mexican American actor was red hot: He had recently gotten nominated for an Oscar for portraying real-life schoolteacher Jaime Escalante in 1988’s “Stand and Deliver” and just wrapped up playing Lt. Martin Castillo on the hip Don Johnson TV series “Miami Vice.”

Miya Iwataki’s face lit up: “He said ‘Mexicans are Asians!’” Olmos had just been the cover story of the L.A. Times Sunday Calendar. Promoting his latest project, the actor talked about Asian people migrating across the Bering Strait into Alaska, down the West Coast and into what’s now Mexico. He concluded, “We Mexicans are Asian.”

He also said he’d always been interested in Asian culture, had studied it, and often blended Asian and Latino traits into many of the characters he played (e.g., Officer Gaff, who folded origami and spoke bits of Chinese and Japanese in the “CitySpeak” language Olmos made up for 1984’s “Blade Runner”).

Luckily, I had a connection to reach Olmos. In early 1988, I had interviewed one of my favorite record producers, Dennis Lambert (“One Tin Soldier” by Coven, “Ain’t No Woman Like the One I Got” by the Four Tops, “Rhinestone Cowboy” by Glen Campbell). He’d mentioned that Olmos was his next-door Encino neighbor, they’d formed a production company, were best friends, and their children played together. I spoke to Lambert’s assistant Maryann, who suggested I write a letter, which she could forward to the actor.

Initially, the “National Day of Protest” rally was set for Saturday, July 8, but it was later pushed back to Aug. 5, which was closer to the one-year anniversary of Reagan’s signing of the bill the previous Aug. 10. Maryann told me the actor was in Bolivia filming a movie and would only be back in L.A. for “a couple days” beginning July 12. On July 7 I sent Olmos another letter, hoping he could make the new date.

On July 12, the first day he returned to Los Angeles, Olmos called me. “I thought this was already taken care of,” he said, sounding a bit confused. “Really?!” Congress had still not allocated money to pay the former internees? I assured him that was the case. He double-checked: This was the bill that was supposed to compensate Japanese Americans who were put in internment camps during World War II? The bill passed but they still haven’t funded it? Yes and yes. Olmos couldn’t believe it. He’d be there!

I mailed him some articles about the status of the appropriations. “I think it would be nice of you to mention in your speech, the fact that you grew up in East L.A. with a lot of Japanese-Americans, and that you were very familiar with the families who came back after the internment camps. I think many of them just think of you as this ‘big star’ and don’t necessarily know the many things you share in common with them.”

He’d do that and more.

As co-chair of the Outreach Committee, I also sent letters to Jane Fonda, Martin Sheen, Casey Kasem, and tried to reach Morgan Fairchild, Dennis Weaver, and Danny Glover. In the end, none of them could make it.

But Olmos — and the cause — was enough. Every local news channel and CBS national covered the “No More Broken Promises” protest.

The Rafu Shimpo estimated a crowd of 1,000. Olmos and I walked in the march around Little Tokyo (as fans stopped to talk to him and shake his hand), which ended in the red-brick plaza outside the Japanese American Cultural & Community Center (JACCC). Co-emceeing the event were Kay Ochi and Frank Emi. Glen Kitayama brought a lot of UCLA students to hold banners, cheer, and loudly show their support.

Olmos told a captive audience he’d been born in the Japanese Hospital in Boyle Heights and grown up in East L.A. with fellow Mexican Americans, Russians, Jews, and Japanese Americans.

He recounted his surprise when I’d told him Congress wasn’t allocating enough money to pay the former internees. “A year later, another broken promise,” he lamented. “What is going on with our [country’s] dignity?”

The actor revealed that he was born at the Japanese Hospital on First Street. When he mentioned the name of the doctor who delivered him, there were a lot of “oohs” and “aahs.”

At one point, Olmos recognized a Japanese American family in the audience and called them out by name. “I didn’t know they were going to be here; they didn’t know I was going to be here,” he said. He reminded us of how interconnected we were, a natural part of each other’s lives.

What a great moment. It helped strengthen the cause that a non-Asian celebrity was calling for justice — for Japanese Americans to finally receive compensation for their pain and suffering.

Through the urging of NCRR and the public, Sen. Daniel Inouye pushed to have the payments become an entitlement program where $500,000 would be paid off the first two years with the remaining $200,000 coming in the third year. On Sept. 29, 1989, the Senate passed the bill 74 to 22.

Finally, we were on our way.

Articles for you