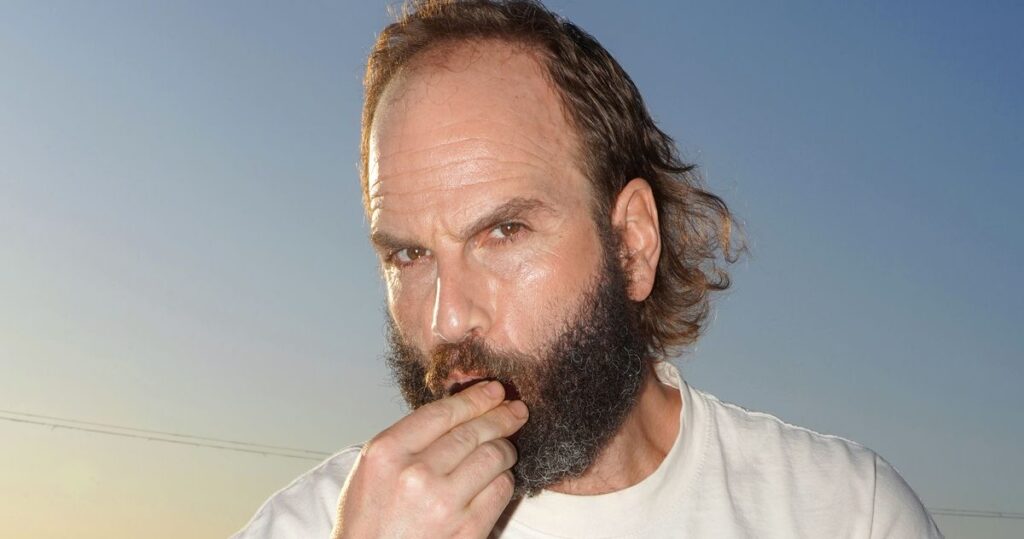

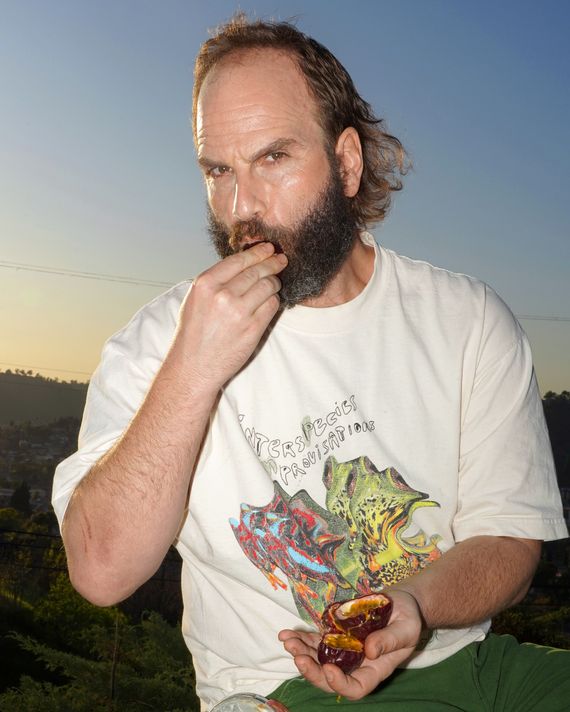

Photo: Jamie Lee Taete for New York Magazine

“I brought you a treat,” Ben Sinclair says as we settle onto a bench in a shady grove within the gates of the Self-Realization Fellowship Lake Shrine on a balmy January afternoon in Los Angeles. Once a hilltop hotel, the estate and its gardens were converted in 1950 into a spiritual center by the yogi Paramahansa Yogananda. Today, monks in ocher robes stroll the sprawling, verdant grounds. Sinclair hands me two kishu mandarins and a Fuji-apple Spindrift, a “rare flavor” he orders online. An elderly monk walks by and gently admonishes us: There’s “no picnicking” at the center. “No problem,” Sinclair says, grinning behind sunglasses. “It’s just some oranges.”

Sinclair’s own spiritual journey followed the 2020 conclusion of High Maintenance, the web series turned HBO show he co-created with his ex-wife, Katja Blichfeld, and starred in as a reserved but unflappable weed-delivery man in Brooklyn. Sinclair has visited Hare Krishna temples, embedded among the followers of Ram Dass in Hawaii, and spent time with members of the Rajneesh movement, immortalized in the documentary series Wild Wild Country. These days, he lives with his girlfriend, chef and cookbook author Jess Damuck, in L.A., where he’s trying out a new form of enlightened navel-gazing: Substack. Sinclair launched his Low Maintenance newsletter in December to narrate his attempts to quit smoking weed; he compares the drug’s hold on him to the intense pull of “a new savory flavor of Chex Mix.” He tells me he recently tried to resist the Buffalo-sandwich variety. “I’m like, Oh, maybe I’m not going to do it today,” he says. No dice: “I definitely ate it, dude.” Despite his best efforts, he knows he “will probably smoke weed again” and “probably enjoy it a lot in the moment.”

It’s his first time on social media since quitting Instagram in 2019 because he also found that addictive and says he couldn’t stop sleeping with fans he met through the app. Now, he catches himself obsessively checking his posts’ performance. Still, he says, compared to drugs, the resulting dopamine spikes are “the lesser of the evil of chemicals.” He sees Substack, where he has quickly amassed thousands of subscribers, as “a cult of personality, where the personality is the topic,” and, given how bound up weed is with his image, the blog is perhaps as much about quitting pot as it is about quitting the Ben Sinclair persona he created. “Identities, like substances, can get you stuck if you hold them too tightly,” he writes. “And weed, the plant itself, is famously sticky.”

A decade ago, Sinclair and Blichfeld, a casting director who won an Emmy for her work on 30 Rock, were hailed for their incisive and vivid portrait of 2010s New York. Through Sinclair’s character — a one-man weed shop who, by virtue of his illegal wares, needs to spend time in intimate settings (usually the apartment of a customer) — the couple crafted moving vignettes about people from all walks of life. The Guy, as Sinclair is known on the show, sells to everyone, stressed-out 20-something assistant and cross-dressing stay-at-home dad alike, witnessing their private joys and pains and shortcomings and judging no one. In retrospect, High Maintenance is a bit of a time capsule — a snapshot of weed’s waning days as a countercultural signifier. Today, the drug feels like it’s at a turning point, as much of what is sold is simply too strong for regular people to enjoy. Mass commercialization has leached away the cool factor. Many legal cannabis ventures enrich hedge funds and politicians, and relatively few benefits accrue to the people who suffered jail time or worse when the drug was criminalized in every state. Seth Rogen and Snoop Dogg may be popular, but they certainly aren’t edgy, and there’s really no stoner-celebrity equivalent for Gen Z. Weed has become a faintly embarrassing millennial concern not unlike blogging.

Sinclair’s awareness of his drug problems started two decades ago, when he was a struggling actor in New York. “I was like, Man, I really like who I am better when I’m on this than when I’m not. I would be better if I just liked who I am,” he tells me. By the end of High Maintenance’s run, Sinclair was smoking mostly by himself. Over the past five years, he has directed and produced TV shows, including Dave and The Resort, but has struggled to find a proper follow-up, pitching a stream of ideas that keep disappearing into development black holes. “I just feel like I’m wasting my time,” he says. High, Sinclair can retreat into a state of being “fascinated” with his thoughts and himself. “But that doesn’t mean you love yourself, and fascination versus love is a very, very important distinction,” he says. In January 2025, Sinclair’s close friend, the screenwriter and director Jeff Baena, died from suicide. Weeks before, Baena had told him that weed made Sinclair less nurturing and attentive. “I admitted to it and then I didn’t stop,” Sinclair tells me. “And then he died and then I still didn’t stop. I was like, Wow, that’s a strong addiction.”

The Low Maintenance Substack is only the latest in a long line of public self-excavations for Sinclair. After college, bored at a temp job, he made a “confessional PowerPoint” charting “how shitty my life was at the time. I had charts of my job, my housing, my STDs.” He chronicled his rejection after a Blue Man Group audition and other depressing milestones and presented the anti-achievements at parties, scoring laughs from his friends.

He has explored a range of spiritual practices, including shaking meditation and ayahuasca ceremonies, seeking a state of metaphysical present tense. “If you’re thinking about the past with any sort of desire attached to it, that’s depression, and in the future, it’s anxiety,” he tells me. He would rather focus on the effervescent “thought forms” that constitute the present. “Apple Spindrift, taste of thing in my mouth. Beautiful garden, great company. Missing my Pilates class. Like, these are what’s happening. I’m just not at Pilates right now, right? It’s just the truth.” In the newsletter, this translates into what he calls a “weird mixture of narcissism and sharing and depending on something greater than myself, and also offering myself completely up to it and being like, ‘Look at me. Don’t look at me.’” He adds, “I’m a fake, but I’m a real fake, right? That feels very spiritual to me.”

As he tries to leave behind one L.A. archetype, the stoner, he’s conscious of the extent to which he’s adopting another, the bearded New Age guru. “I have the moral weirdness of a guru and also the huggy feeling that you get from a guru.” The difference? “I’m willing to be like, I like to watch rim jobs” on porn sites. Sinclair compares himself to Ram Dass, “a total hornball. He was, like, in the closet hooking up with twinks” while teaching at Harvard, he says. For a time, Sinclair became convinced that playing Ram Dass onscreen should be his next big project. “I was very headstrong about it. I went into the community essentially being like, ‘I’m him, I’m the next one.’” He rubbed some of Ram Dass’s followers the wrong way. “I was truly a bull in a china shop to the point where I’m like, Ah, that’s a pretty good story,” Sinclair tells me. “Being a bull in a china shop with the spiritual community, where they end up hating me, is actually a more interesting story than some period piece being like, ‘Wow, isn’t Ram Dass amazing?’”

In the late afternoon, as the sun cast long shadows through the monastery’s trees, a monk told us quietly we’d have to leave. “Your energy is very monkish, I have to say,” Sinclair tells him, smiling. He gives me a ride home in a light blue Fiat with the license plate SPRDLOV and a bumper sticker that reads be there later, a play on the Ram Dass slogan “Be Here Now.” The Fiat belongs to a friend of Sinclair’s named Carl, a Ram Dass acolyte he met at the Hawaii compound. The half-smoked joints in the cupholder, he insists, are Carl’s, not his.

This story has been updated to correct the color of the Fiat Sinclair drove.

Thank you for subscribing and supporting our journalism.

If you prefer to read in print, you can also find this article in the February 9, 2026, issue of

New York Magazine.

Want more stories like this one? Subscribe now

to support our journalism and get unlimited access to our coverage.

If you prefer to read in print, you can also find this article in the February 9, 2026, issue of

New York Magazine.