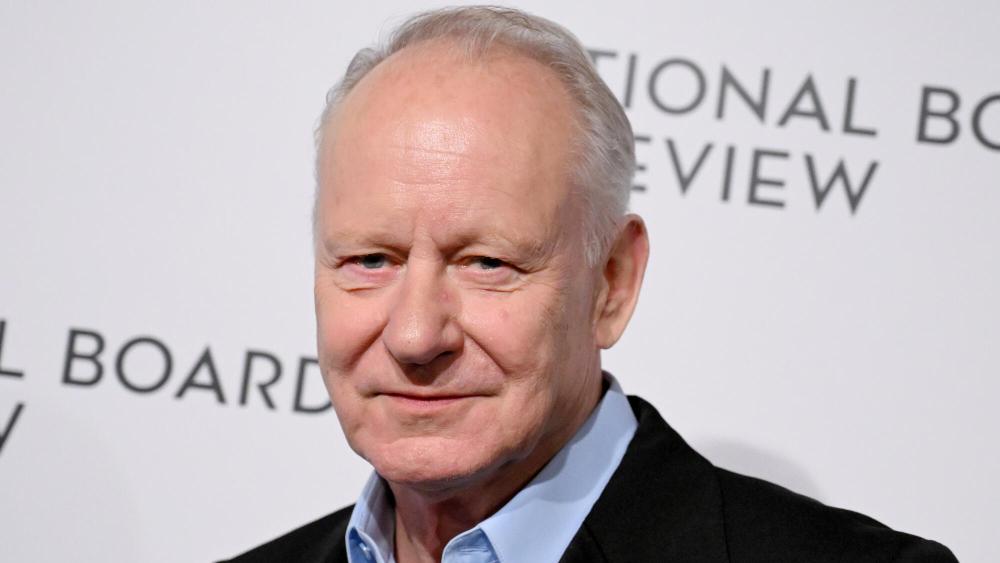

Stellan Skarsgård didn’t know how special it was going to be.

The role, the film, and the unlikely awards journey that would follow. But sitting with the results — a first Academy Award nomination after more than 50 years in film — the Swedish actor wears the recognition with the same precision he brings to every performance.

Skarsgård is nominated in the best supporting actor category for his role in Joachim Trier’s Norwegian-language drama “Sentimental Value,” in which he plays a Gustav Borg, a film director and a father navigating fractured family bonds alongside a cast that includes Renate Reinsve, Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas and Elle Fanning. The film earned nine Oscar nominations in total, a remarkable reversal after being shut out of the Actor Awards (formerly SAG) entirely.

“We got snubbed for the SAG Awards, and then suddenly we got nine nominations,” Skarsgård says. “That’s better.”

His performance is anchored in what he calls the film’s defining quality: everything that goes unspoken. “So much of this film is about what is not on screen — what is not in dialogue, not in the script,” he shares. “It’s all atmosphere, all our memories and personalities. Joachim extracts that from who we are and plays with it.”

For an actor who made his professional debut as a child, appeared in more than 200 film and television productions and collaborated with directors from Lars von Trier to Denis Villeneuve to Gus Van Sant, the nomination is a milestone and, he suggests, something of a surprise.

Although he doesn’t have any projects lined up, he’s not idle. He is, as ever, watching, reading, thinking about people — which, he argues, is the entire point of cinema.

“For thousands of years, people have been very much interested in people,” he says. “That curiosity will never leave us.”

Read excerpts from his interview below, which has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Stellan Skarsgård in “Sentimental Value”

Courtesy Everett Collection

You received nine Academy Award nominations for “Sentimental Value” after being shut out of the SAG Awards entirely. How did you process that whiplash?

It feels good — better than not being one (a nominee). You have to be prepared for everything. There’s no way to predict these things. We got snubbed for the SAG Awards, and then suddenly we got nine nominations. That’s better.

This role has been called one of the finest of your career. What made it possible to reach something so singular?

You are allowed to say it’s one of the best roles of my career — if not the best. It’s not only the role as written on the page. It became what it became through Joachim’s way of letting me do my job as fully as possible. He’s watching everything, keeping it, editing it, making it better. It’s fantastic. I’m very lucky to have done this role.

Did you sense in those early days on set that something special was happening?

I didn’t know how special it was. I didn’t know how wonderful the other actors would be, and I didn’t know how great the connection we made would become. So much of this film is about what is not on screen — what is not in dialogue, not in the script. It’s all atmosphere, all our memories and personalities. Joachim extracts that from who we are and plays with it.

You grew up watching one film a week on Swedish television. Which early films stayed with you and shaped the actor you became?

My father always made sure I saw the best films: old films, black-and-white films, Italian neorealism, French New Wave. One of the films I really got hooked on was “Children of Paradise” — “Les Enfants du Paradis” by Marcel Carné.

In that film, Jean-Louis Barrault plays a mime artist in a theater company in early 19th century France. He’s performing onstage, and at the same time, the woman he loves is standing in the wings with another man. He sees it for the first time and understands she loves someone else. The way his face — thick with white makeup — cracked in that moment: That was wonderful for me.

It stands as an image of what you want to achieve. You want to see the cracks in the facade of people, and you can do that in cinema as in no other form.

For many American audiences, Lars von Trier’s films — “Breaking the Waves,” “Dancer in the Dark,” “Dogville,” “Melancholia” — were the introduction to your work. What was it like being in that world?

He said to me once, “Stellan, I know now what films I’m making.” I said, “Yeah? What films are you making, Lars?” He said, “I’m making the films that haven’t been made.” Yes, Lars. You’re doing that.

Every film is like nothing else, and that’s so wonderful. When I worked with him for the first time — I had made maybe 30 films at that point, I thought I knew filmmaking — here comes this guy and he breaks every rule. The way he cuts, the way he frames.

His first five films were beautiful but ice-cold because they were overthought, and the actors were given no freedom at all. But then he changed. On the set of “Breaking the Waves,” he had signs everywhere that said, “Make mistakes.” We could do anything we wanted.

What he does is release the true life of the actor. Life is always irrational — you cannot plan it — and it’s in those irrational, surprising moments that true life comes through.

Do you see parallels between Lars von Trier and Joachim Trier as filmmakers?

You’re absolutely right. On the most important thing, they are doing the same: letting you free, letting you bleed out your own emotions, and then using them brilliantly in the edit.

Lars von Trier is more story-oriented and perhaps less interested in the purely psychological surprises. But it’s the same fundamental thing. They are like two different painters working with different materials and different colors.

“Good Will Hunting” introduced you to a generation of American audiences, including this interviewer. What do you remember of working with Robin Williams and Gus Van Sant?

With Gus, it was wonderful because he didn’t block the scenes. We blocked them ourselves in rehearsal, and then he said, “I’ll put the camera here — let’s start.” He took the first take and said, “Oh, good. I like that. Let’s do it again.” And then he said exactly the same thing for 10 takes.

You felt like he truly loved it — he just wanted to see more. And you get more courageous, you get new ideas, you want to try new things.

Robin was all over the place, of course, because he couldn’t help improvising and doing wild things. His brain was constantly feeding him comic and dark ideas, like a waterfall showering over you. But what Gus got by doing 10 takes like that was incredible material. He could cut Robin into a very nasty guy if he wanted, a very funny guy, a very sad guy, or something in between.

What was it like working alongside Renata Reinsve, Inga and Elle Fanning in “Sentimental Value?”

Renate is an exceptional talent. She has a range and a depth that knocks everyone over who stands opposite her. I was glad to be able to live up to her.

And then there’s Inga, who I had never seen before. She’s amazing. She almost does nothing, and yet she grows into the center of the film — not only the voice of reason, but the voice of love.

And then Elle — a young woman with a background like mine, starting as a child actor. She came in wide open to these weird Norwegians and the weird Swede she’s going to work with, without any preconceived ideas about what it would be. And then she opens up totally and does very, very difficult things.

She’s playing an actress who is very good but not quite right — and that is very hard. I’m not saying much in that final scene. I was just looking at her. Watching her, it was heartbreaking.

What is your feeling about the current state of cinema — and the growing presence of AI in the industry?

For thousands of years, people have been very much interested in people. Describing people is what theater does, what film does — and what we do best.

In film — even better than in television — you can describe all the unspoken words, all the unspoken facets of a relationship that are almost impossible to explain but are still there. We will always be curious about other people. That curiosity will never leave us.

What form it takes, how it will be produced — maybe some people will be happy enough with what AI can produce, and some will not. But I think the main problem for the moving image industry today is the concentration of capital. And the concentration of capital is the problem for every industry, for humanity. AI is nothing without the men behind it. AI is owned by the tech barons standing right behind power.

You could have had a father-son Oscar moment this season with Alexander, who was on the circuit for “Pillion.” What was that time together like?

We were actually hoping Alexander would get nominated for “Pillion” so we could have been in the same category for the first time. I had so much fun with Alexander at the beginning of the season, when we were doing the awards circuit together — drinking, joking, watching films. It was a beautiful time, and I wish Bill had been part of it.

After 50 years in film, what remains at the core of what you love about this work?

I think it’s being on the set — creating something together with other people. I’m not really a monologue actor. I’m a dialogue actor. I take my energy from the other actors and give my energy back to them. I think what’s most interesting is what happens between people.

But I also like the crew. I know exactly what everyone’s different jobs are. I walk on set, I talk to people, I joke with them. I have this feeling of family around me that makes me more courageous.

Variety’s “Awards Circuit” podcast, hosted by Clayton Davis, Jazz Tangcay, Emily Longeretta and Michael Schneider, who also produces, is your one-stop source for lively conversations about the best in film and television. Each episode, “Awards Circuit” features interviews with top film and TV talent and creatives, discussions and debates about awards races and industry headlines, and much more. Subscribe via Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, Spotify or anywhere you download podcasts.